Common Animals of Unimak area:

The fauna of the Aleutian and Alaska Peninsula area was surveyed and documented in 1936-38 by Murie and Scheffer. They offer interesting details about the animals' distributions and uses and their book is used as a guide for this page. The complete book can be downloaded for free here. Probably the only thing that has changed much since 1938 is the number and perhaps distribution of some of the animals. The Unimak area has a large number of animal species and only a small percentage can be covered here. This area of the world has prolific wildlife due to the great productivity of the North Pacific-Bering Sea marine-island environment.

List of Animals on this website: (Click on animal name to go to the entry on this page.)

Fish:

Red or Sockeye Salmon

Silver or Coho Salmon

Dog or Chum salmon

Pink or Humpback Salmon

King or Chinook Salmon

Pacific Halibut

Cod

Marine Invertebrates:

Bidarki or Black Katy Chiton

Sea Urchin

Blue MusselMarine Mammals:

Sea Otter

Killer Whale (Orca)

Sea Lion

Gray Whale

Harbor Seal

Birds:

Black Brant

Emperor Goose

Canadian Goose

Common Teal

Mallard

Harlequin or Rock Duck

Red Breasted Merganser or Fish Duck

Willow Ptarmigan

Magpie

Bald EagleLand Mammals:

Brown Bear

Caribou

Red Fox

Weasel

Land Otter

Fish Species of the Unimak Area:

Five Salmon Species are found in the Unimak area:

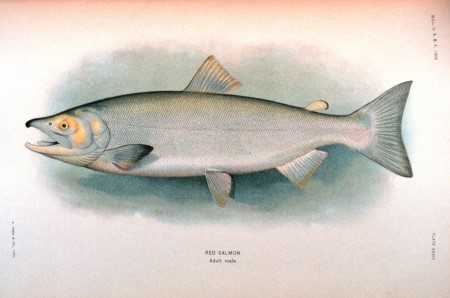

The red salmon or sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka), is the most highly prized salmon in the Unimak area and has the highest commercial value. It is an anadromous species of salmon found in the Northern Pacific Ocean and rivers discharging into it. Red salmon is the third most common Pacific salmon species, after pink and chum salmon.

Reds are blue tinged with silver in color while living in the ocean. Just prior to spawning both sexes turn red with green heads and sport a dark stripe on their sides. Males develop a hump on their back and the jaws and teeth become hooked during their move from salt to fresh water. Reds spawn mostly in streams having lakes in their watershed. The young fish, known as fry, spend up to three years in the freshwater lake before migrating to the ocean. Migratory fish spend from one to four years in salt water, and thus are four to six years old when they return to spawn. Navigation to the home river is thought to be done using the characteristic smell of the stream, and possibly the sun.1 Sockeye salmon are one of the smaller species of Pacific salmon, measuring 18 to 31inches in length and weighing 4-15 pounds.7

Red salmon first appear around False Pass at Swede's Lake on the Ikatan Peninsula in late May and are prized as the first fish of the season.

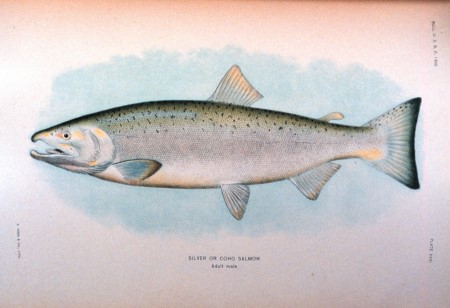

The silver or coho salmon, (Oncorhynchus kisutch), (from the Russian кижуч kizhuch) is a species of anadromous fish in the salmon family. Coho salmon are also known as silver salmon or "silvers" in the Unimak area.

During their ocean phase, Coho have silver sides and dark blue backs with spots. During their spawning phase, the jaws and teeth of the coho become hooked. They develop bright red sides, bluish green heads and backs, dark bellies and dark spots on their backs after they go in to fresh water. Sexually maturing coho develop a light pink or rose shading along the belly and the males may show a slight arching of the back. Mature adults have a pronounced red skin color with darker backs and average 28 inches (71 cm) and 7 to 11 pounds (3.2 to 5.0 kg) occasionally reaching 36 pounds (16 kg).2

Silver salmon are the species usually chosen for putting up salt salmon in barrels in the fall in the Unimak area. Since the demand for commercial salt salmon has fallen off, most salting is now done for subsistence use.

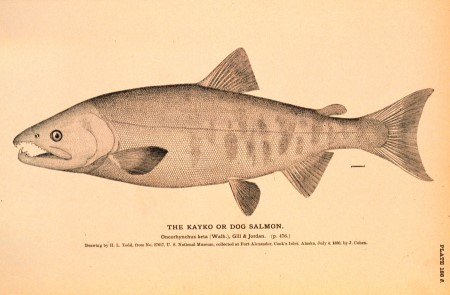

The dog or chum salmon, (Oncorhynchus keta), is a species of anadromous fish in the salmon family. The name Chum salmon comes from the Chinook Jargon term tzum, meaning "spotted" or "marked", while "Keta" comes from the Evenki language of Eastern Siberia via Russian.

They have an ocean coloration of silvery blue green. When adults are near spawning, they have purple blotchy streaks near the caudal fin. Spawning males typically grow an elongated snout or kype and have enlarged teeth. Chums average 24-28 inches and 10-13lb; males usually larger than females.6

Most Chum salmon spawn in small streams and intertidal zones. They spend one to three years traveling very long distances in the ocean. They die about two weeks after they return to the freshwater to spawn.

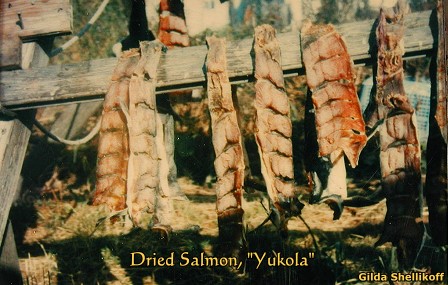

Chums are the salmon usually used to make dried fish called "Yukola" in the late summer from local runs in the Unimak area. Because of the usual low oil content, this dried fish can be kept in storage for winter use without refrigeration.3

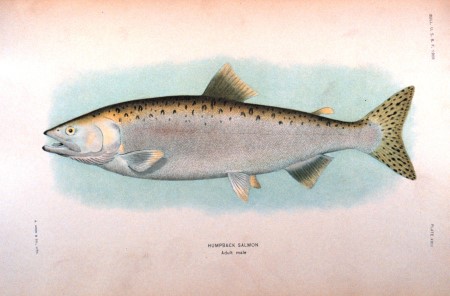

Pink salmon or humpback salmon, (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), (from a Russian name for this species gorbuša, горбуша) is a species of anadromous fish in the salmon family. It is the smallest and most abundant of the Pacific salmon. In the Unimak area these salmon are often called "humpies".

Pink salmon have a strict two year life cycle, thus odd and even-year populations do not interbreed. Adult pink salmon enter spawning streams from the ocean, usually returning to the water course where they originated. Pink salmon spawn in coastal streams and some longer rivers, and may spawn in the intertidal zone or at the mouth of streams if freshwater is available.4 Pink salmon are the smallest of the Pacific salmon found in North America weighing on average between 3.5 and 5 pounds, with an average length of 20-25 inches.8

Pinks (along with Chums) are now the lowest value per pound commercial salmon in the Unimak area. They are usually caught in beach seines by local fishermen and the run is strongest every other year when they can appear in large numbers.

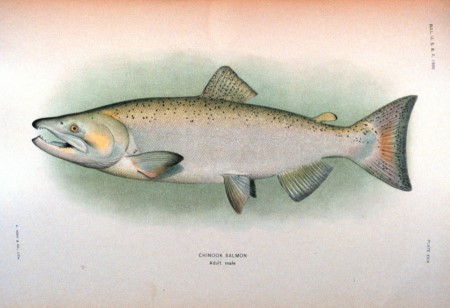

The king or chinook salmon, (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) (derived from Russian чавыча, which in turn comes from a common name used among natives in Alaska and Siberia), is an anadromous fish that is the largest species in the salmon family. Locally, they are known as kings.

The king is blue-green or purple on the back and top of the head with silvery sides and white ventral surfaces. It has black spots on its tail and the upper half of its body. Its mouth is often dark purple. Adult fish range in size from 33 to 36 in (840 to 910 mm) but may be up to 58 inches (1,500 mm) in length; they average 10 to 50 pounds (4.5 to 23 kg) but may reach 130 pounds (59 kg).

King salmon may spend 1 to 8 years in the ocean (averaging from 3 to 4 years) before returning to their home rivers to spawn.5 Since there are no large river systems in the Unimak area, the few kings that are caught locally are traveling fish, on their way to the river of their birth to spawn.

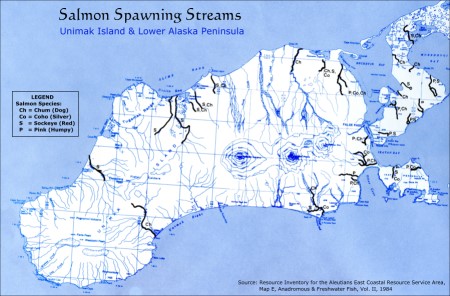

Salmon spawning streams in the Unimak area are shown on the map on the right. (Click on map to see a larger version.) In general, the most productive streams are on the north side of Unimak and at the head of Morzhovoi Bay.

Red salmon or sockeyes spawn and are caught in commercial numbers from local runs mostly on the north side at Urilia Bay, Swanson's Lagoon and the head of Morzhovoi Bay. Smaller red runs are at Hot Springs, Sankin Bay, Deadman's and Swede's Lake.

Silvers or Cohos spawn and are caught near Swanson's, Mike's Creek, Big River, Lazaref, Swede's Lake, Salmon Ranch and Middle Lagoon.

Humpies or Pinks spawn and are caught near Mike's Creek, Sourdough, Big River, Otter Cove, Swede's Lake, Salmon Ranch, Sankin, Deadman's, Trader's Cove, Boiler Point.

Chums or Dogs spawn and are caught near Urilia Bay, Otter Point, Swanson's, Mike's Creek, Sourdough, Big River, Lazaref, Lutke, Trader's Cove, Hot Springs & Hungry's.

Dried salmon, called Yukola locally, has been one of the traditional mainstays of the Unangan/Aleut diet. The name comes from Russian: (юкола) meaning dried fish. The original Unangan name for yukola was Udax^. It is usually made in late summer from chum salmon but sometimes pinks are used. Oily salmon cannot be used as the oils turn rancid when exposed to the air.

Yukola is simply air-dried salmon, without any smoking. Some people put it in a salt brine briefly before hanging to dry. These days, many people have special sheds with window screen to exclude the flies that can present a big problem during the drying process because they lay their eggs on the fish. The important thing is to have lots of fresh air movement over the fish so it will dry nicely. Yukola will keep well for winter use as long as it is kept cool and dry.

Yukola can be eaten as is and was traditionally eaten with tea and bread. The salmon skin is often eaten after being made crisp over the fire.

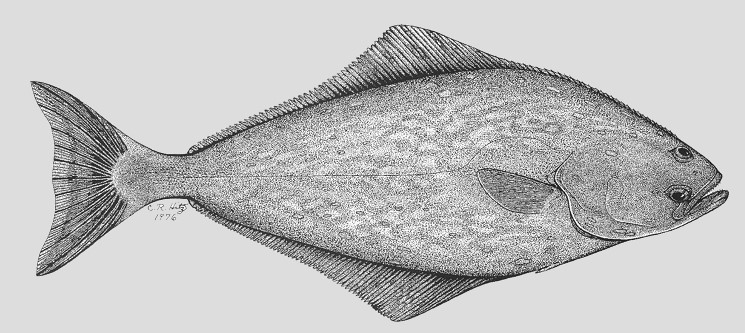

Pacific Halibut: Hippoglossus stenolepsis

The Pacific halibut is found on the continental shelf of the North Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea. The Unimak area has always had an important halibut fishery, first for subsistence and later commercial. The major nursery for juvenile halibut is found in the southwest Bering Sea, north of Unimak Island. 24

Geographic range: Coastal waters of Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and into northern California. The center of abundance is the central Gulf of Alaska, particularly near Kodiak Island.

Habitat: Juveniles (1 inch and larger) are common in shallow, near-shore waters 6.5 to 164 feet deep in Alaska and British Columbia. Halibut move to deeper water as they age and migrate primarily eastward and southward.

Life span: Females and males both live to be quite old. The oldest halibut on record (IPHC) was a 55 year old male, but halibut over the age of 25 are rare.

Food: Juveniles eat small crustaceans and other bottom-dwelling organisms. Mature halibut prey on cod, pollock, sablefish, rockfish, turbot, sculpins, other flatfish, sand lance, herring, octopus, crabs, clams, and occasionally smaller halibut.

Growth rate: Both female and male halibut grow about 4 inches per year until about age 6. From then on, females grow faster and reach substantially greater sizes. Growth rates of both sexes have varied greatly over the last century and depend on abundance of both halibut and competing species.

Maximum size: Halibut can weigh over 500 pounds and grow to 9 feet. Males are smaller than females. Females mature around 12 years old; males mature around 8 years old.

Reproduction: A 50-pound female can produce about 500,000 eggs; a female over 250 pounds can produce 4 million eggs. Females spawn once per year. They release their eggs in batches over several days during the spawning season. Eggs hatch after 12 to 15 days. The larvae slowly float closer to the surface where they remain in the water column for about 6 months until they reach their adult form. They then settle to the bottom in shallow water.

Spawning grounds: In deep water (approximately 600 to 1,500 feet) along the continental slope, concentrated at a number of locations in the Bering Sea, Aleutian Islands, Gulf of Alaska, and south to British Columbia.

Migrations: Adults migrate seasonally from shallow summer feeding grounds to deeper winter spawning grounds.

Predators: Marine mammals and sharks sometimes eat halibut; halibut are rarely preyed upon by other fish.28The Alaska commercial halibut fishery has been managed under an Individual Fishery Quota (IFQ) system since 1995. The IPHC sets the seasons and catch limits annually, and the catch limit is apportioned among U.S. fishermen based on individual quota shares. An IFQ permit authorizes participation in fixed-gear harvests of Pacific halibut off Alaska. The permits are not specific to vessels. Permits are issued annually, at no charge, to persons holding fishable Pacific halibut Quota Share (QS). QS was initially issued to persons who owned or leased vessels that made legal commercial fixed-gear landings of Pacific halibut during 1988-1990 off Alaska. QS is transferable to other initial issuees or to those who have become transferable eligible on NMFS' approval of an Application for Transfer Eligibility Certificate. Once issued to a person (at no charge), QS is held by that person until it is transferred, suspended, or revoked.25

Commercial halibut fishing gear consists of units of leaded ground line in lengths of 100 fathoms (600 ft; 183 m) referred to as “skates.” Each skate has approximately 100 hooks attached to it. “Gangens,” or the lines to which the hooks are attached are either tied to or snapped onto the ground line. A “set” consists of one or more baited skates tied together and laid on the ocean bottom with anchors at each end. Each end has a float line with a buoy attached. Hooks are typically baited with frozen herring, octopus, or other fresh fish. Depending on the fishing ground, depth, time of year, and bait used, a set is pulled 2 to 20 hours after being fished. Longlines are normally pulled off the ocean floor by a hydraulic puller of some type. The halibut are cleaned soon after being boated and are kept on ice to retain freshness.26

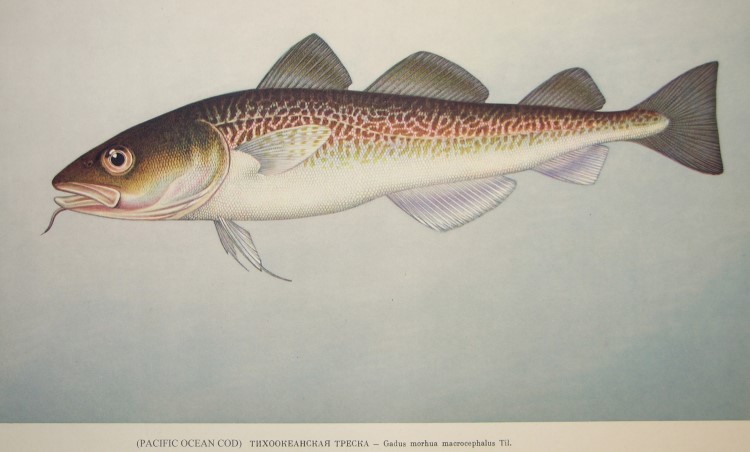

Pacific Cod: Gadus macrocephalus

Cod has always been common in the Unimak area but it essentially disappeared between about 1940 and the late 1950's. Cod was the primary commercial fish in the Sanak area from about 1900 until around 1940 and permanent codfish stations were established at Company Harbor and Pauloff Harbor (see village information on this website). Another half-dozen codfish stations were established in the area before 1920, but they were abandoned after only a few years in operation. The schooner-based cod fishery from the Puget Sound area of Washington also operated in the Unimak area, but their influence locally was very minor. Beginning in the early 1970's, cod began to reappear in the Unimak area. About 1991, fishermen from False Pass and King Cove resumed commercial cod fishing, using pots and jig. The cod catch is processed in King Cove.

Habitat: Cod are demersal, living near the bottom, and concentrate on the shelf edge and upper slope (328 to 820 feet deep) in the winter and move to shallower waters (less than 328 feet deep) in the summer. Pacific cod have been found as deep as 2,871 feet. Adults and large juveniles prefer mud, sand, and clay habitats.

Life span: Relatively short-lived with a maximum age of about 19 years

Food: Clams, worms, crabs, shrimp, and juvenile fish

Growth rate: Moderately fast growing Maximum size: Over 6 feet. Females mature at a length of 1.6 to 1.9 feet and at about 4-5 years of age.

Reproduction: Females have high reproductive potential - a mature female can produce over 5 million eggs. Pacific cod are single batch spawners, releasing all of their ripe eggs in a single spawning event within a few minutes.

Spawning season: From January through May, depending on location

Spawning grounds: On the shelf edge and upper slope (328-820 feet deep)

Migrations: Individual adults have been found to move more than 621 miles. Pacific cod also move seasonally from deep outer and upper shelf spawning areas to shallow middle-upper shelf feeding grounds. They are a schooling fish.

Predators: Predators include halibut, sharks, seabirds, and marine mammals.

Distinguishing characteristics: Pacific cod are brown or grayish with dark spots or patterns on the sides and a paler belly. They have a long chin barbell (a whisker-like organ near the mouth like on catfish) and dusky fins with white edges.27Commercial codfishing regulations are complex and controlled by the ADF&G (Alaska Dept. Fish & Game) in state waters29 and the NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service) in waters of the EEZ.30 Since cod is usually fished in seasons different from salmon, local commercial fishermen now often fish nearly the year around.

Marine Invertebrates:

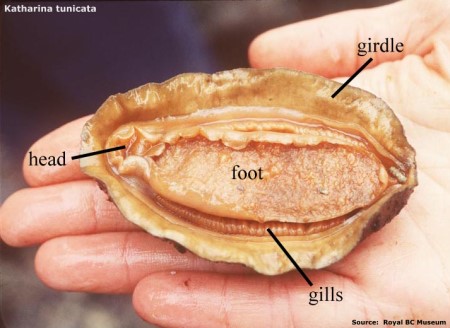

Bidarki: Black Katy Chiton: Katharina tunicata"Katharina tunicata is fairly common. Many individuals were noted at Umnak Island in shallow tidal pools and at Amlia Island on a rocky, kelp-covered ledge. The body is black and leathery, with a row of eight plates down the back. Its local name "bidarka" is also applied to the skin boat of the Aleuts. The natives prepare the chiton for eating by boiling it in sea water for 10 minutes, then peeling off the skin, scales, and viscera and soaking in fresh water. The general color of the live chiton is dark brown with brown and tan plates."9

Bidarkis are named after the Russian name for the Aleut Iqyak or kayak (literally, little baidar or skin boat) due to its shape. These black chitons are relished by local people and are harvested off the rocks on low tide. The "foot" is often eaten raw. Bidarkis tend to move away from the light so that one usually has to look under rocks and into crevices to find them.

Chitons live by grazing on algae that grows on rocks. "The mouth is located on the underside of the animal, and contains a tongue-like structure called a radula, which has numerous rows of 17 teeth each. The teeth are coated with magnetite, a hard ferric/ferrous oxide mineral. The radula is used to scrape microscopic algae off the substratum. The mouth cavity itself is lined with chitin and is associated with a pair of salivary glands. Two sacs open from the back of the mouth, one containing the radula, and the other containing a protrusible sensory subradula organ that is pressed against the substratum to taste for food."13

"Cilia pull the food through the mouth in a stream of mucus and through the oesophagus, where it is partially digested by enzymes from a pair of large pharyngeal glands. The oesophagus in turn opens into a stomach with where enzymes from a digestive gland complete the break down of the food. Nutrients are absorbed through the linings of the stomach and the first part of the intestine. The intestine is divided in two by a sphincter, with the latter part being highly coiled and functioning to compact the waste matter into faecal pellets. The anus opens just behind the foot."13

Green Sea Urchin: Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis

Local name: Sea Egg"Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis, the green sea urchin, is one of the most common inshore animals of the Aleutian Islands. In many places it is possible to look down from a boat through the clear water and see thousands of individuals side by side in a submarine garden of green. <N.B.: This was 1938 when the urchin's predator, the sea otter, had been exterminated in this area.> It occurs on rocky bottoms more frequently than on sand. Several specimens dredged from deep water (30 fathoms) off Sanak Island were a faded brown in color. Sea urchin spines are so predominant in the refuse heaps of ancient Aleut villages that the middens are grayish in color. Sea urchins are eaten by the present-day natives. A small child was seen sucking the brown contents of one at Nikolski. The shell was cracked open and the orange part (gonad and liver) was eaten with the fingers. Sea urchins do not seem to be particularly palatable to fish. For example, in 20 cod stomachs examined at Chuginadak Island, only 1 small urchin was found. The occurrence of sea urchin remains in sea-otter, blue-fox, and sea-gull droppings has been mentioned elsewhere."

"According to Clark, no other species of Strongylocentrotus occur in the Aleutians. A fisherman stated that he had seen the large purple S. franciscanus at Sitka, Alaska, but he had not seen it in the Aleutians."18 pg. 373

The Sea Otter-Sea Urchin-Kelp inter-relationship. Sea urchins are grazers on kelp and therefore have profound effects on the Aleutian coastal ecosystem. Studies in the last twenty years have clarified the importance of the sea urchin within this ecosystem. There is a cascading effect within the ecosystem when the role one of the key players is changed. "Regardless of the ultimate cause, sea otter population declines and the consequent collapse of kelp forest ecosystems almost certainly have been driven by events in the offshore oceanic realm. Our proposed explanation involves a chain of ecological interactions, beginning with reduced or altered forage fish stocks in the oceanic environment, which in turn sent pinniped populations into decline. Pinniped numbers eventually became so reduced that some of the killer whales who once fed on them expanded their diet to include sea otters. This shift in killer whale foraging behavior created a linkage between oceanic and coastal ecosystems and in so doing transformed coastal kelp forests from three- to four-trophic-level systems, thereby releasing sea urchins from the limiting influence of sea otter predation. Unregulated urchin populations increased rapidly and overgrazed the kelp forests, thus setting into motion a host of effects in the coastal ecosystem."16

Blue Mussel: Mytilus edulis"The larger, abundant mussels are of two kinds. Mytilus edulis, the edible or blue mussel, is smooth and regular and is purplish blue to black in color with a bluish nacre. The umbo is apical, unlike that of the horse mussel. The edible mussel is used for food by the natives and is said to be best when there is a roll of snow-white fat on either side of the body. When yellow and lean, the flesh is unpalatable. Volsella modiolus, the horse mussel, can be distinguished from the former by its larger, thicker shell and by the presence of a brown periostracum. The umbo is never at the apex, and the nacre is gray. The horse mussel usually grows solitary or in clusters of a few, while the edible mussel may cover the rocks in an area many feet in diameter. Both attach to rocks by a thready byssus, but the horse mussel usually is partly buried in sand. (A third large mussel, Mytilus californicus , was collected only once — at a depth of 30 fathoms off Sanak Island.)"9 pg. 382

Ordinarily, the blue mussels are excellent food, steamed for about 20 minutes until open and served with butter. But, a cannery worker died in False Pass in 1954 from eating mussels contaminated with "Red Tide" (paralytic shellfish poisoning or PSP15) caused by the dinoflagellate plankton, Gonyaulax catenella. PSP is not common in the Unimak area, but does show up occasionally and there are stories of people getting sick and some deaths from eating clams and mussels. The following is an excerpt from the log of Dr. J. Clark, physician at the cannery hospital: "Patient seen by physician at 4:45 pm and found suffering severe abdominal pain and nausea and vomiting. Man expired at 5:00 pm same day. On-set of illness between 2:00 pm and 4:45 pm."14

Birds of the Unimak Area:

Emperor Goose: Philacte canagicaLocal name: Beach Goose

Aleut names: Attu: Il-d-ghir-hch

Atka: Kd-ghu-mung

Qdmgan (Jochelson)"The emperor goose apparently does not commonly nest in the Aleutian Islands, nor on the Alaska Peninsula, but at least one record of nesting was established. During June 1925, a Bureau of Fisheries boat had stopped for a short time at Amak Island, on the way to Port Moller. The pilot informed me that during that stop at least three pairs of emperor geese were seen. On July 10, 1925, during a visit to Amak, I found the remains of a young emperor goose in a bald eagle nest. The feet, stomach, and numerous pinfeathers were present in the nest, and were collected. This appears to be the southernmost nesting locality."

"It is well known that the emperor goose is largely a beach feeder; in fact, it has earned the local name "beach goose." Yet, it is reported as occasionaly feeding on the berries of the tundra, notably Empetrum nigrum."

".... Sometime early in September, the emperor geese begin to arrive from the north in the vicinity of Izembek Bay. And, according to the enthusiastic accounts of local residents, these emperor geese are almost as numerous as the cackling geese before the latter declined in numbers. At Port Moller, emperors are said to arrive as early as the latter part of August. They congregate on Nelson Lagoon, Izembek Bay, head of Morzhovoi Bay, locally in Isanotski Strait, St. Catherine Cove, Swanson Lagoon, and Urilia Bay. Most of these geese move westward some time in November. Incidentally, Swarth (1934) states that emperor geese were present on Nunivak Island, to the north, as late as October 29, 1927. The Attu chief said that they arrive at that westernmost point in the Aleutians late in October."9

The emperor or beach goose is relatively common on the beaches of Isanotski Strait in winter.

Murie's complete account of the emperor goose is here.

Canada Goose: Branta canadensis

"Branta canadensis leucopareia

Branta canadensis minimaAleut names: Attu: Legch

Atka: Luck or lug-ach, or lagix (Jochelson)Resident whites: land geese

The white-cheeked geese were formerly common migrants throughout the Aleutian Islands area and nested on many of the islands. These populations now (1936, 1937, and 1938) have been universally reduced."

"According to local information, they generally arrive at Unimak and the Alaska Peninsula about September 1, but they do not become numerous until 1 or 2 weeks later. Then, they assemble in surprising numbers and congregate at Urilia Bay, Swanson Lagoon, and St. Catherine Cove, all on Unimak Island, and at Izembek Bay, head of Morzhovoi Bay, Nelson Lagoon, and Port Moller on the Peninsula. In 1942, Gabrielson reported the first fall migrant at Izembek Bay as early as "late in July."

"In 1925, accounts of the coming of the geese in "countless thousands" and "millions" testified to unusual concentrations, and it is safe to say that this area is the prinicpal gathering place for geese nesting along the shore of Bering Sea northward, as well as those from the Aleutians proper. The emperor goose and the 2 forms of the Canada goose all assemble here — of the two, the Canada geese are in the majority."

"This area seems to be a place where the geese can fatten in the fall before continuing to their wintering grounds. They are said to feed to some extent on eelgrass; minima and leuco-pareia feed mostly on crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) and other berries and spend so much time on the slopes seeking these foods that they are known locally as "land geese" — distinguishing them from the "beach goose," which is the local name for the emperor goose.

"The geese become very fat and leave for the south about November 1, though according to some reports it is as late as November 15 or 20. Probably, the earlier date is the more usual one. In 1942, according to Gabrielson, the geese departed rather suddenly, eastward, on November 20."9

Murie has a long and detailed account of this "Land Goose" in which he says that Aleuts further out west "domesticated" these geese by clipping their wings to secure food for later in the year. You can read Murie's complete account here.

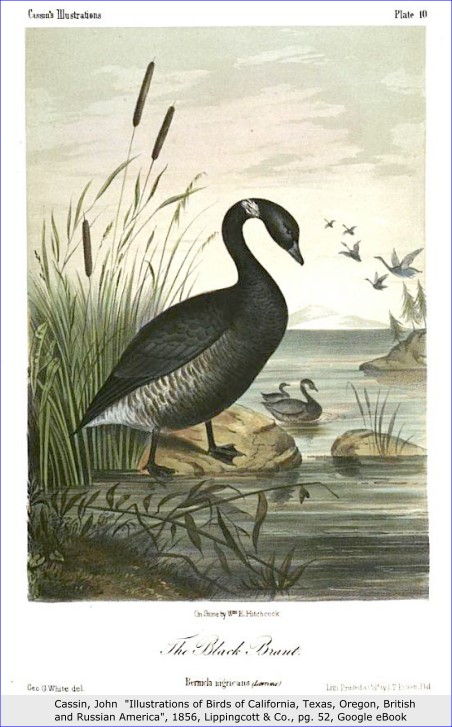

Branta nigricans: Black BrantAleut name: "Attu : Agru-ge la-ghe

Russian, Yana district: Njemok (Pleske)The black brant is only a migrant in the Aleutian district, but it occurs in considerable numbers. <Brant nest mostly on the Y-K Delta.>32 In 1936, we were told at Port Moller that the brant appear there in April, and we received the same information for the Chignik area. We had seen them on northward migration near Seymour Narrows, British Columbia, on April 24, and on Queen Charlotte Sound on April 25. Donald Stevenson, in 1925, said that he had seen them at King Cove "late in April."

Apparently, the many bays at the western end of Alaska Peninsula are favorite gathering-places for black brant in migration. In 1925, Stevenson and I observed them on Izembek Bay, where they were present on May 20 in small flocks, on the water and flying from point to point. However, some flocks contained as many as 200 birds, and about 5,000 black brant were estimated for the entire bay. The following day, at the east end of the bay, there were only a few groups....

In 1943, Gabrielson found black brant on the Sanak Islands on April 30, and the next day, at King Cove, he saw 100, or more, heading toward Cold Bay. In 1944, residents at Port Moller reported the first spring flight on April 26.

A. C. Bent (1925) quotes Chase Littlejohn as saying that the brant move westward along the Alaska Peninsula, 1 or 2 miles offshore, turn into Morzhovoi Bay, and thence go into the Bering Sea. This probably outlines the spring migration fairly accurately." 9

"In late October or early November, brants depart Izembek Lagoon during low pressure systems that generate the favorable southerly winds for transoceanic migration. When meteorological conditions are appropriate, nearly all brants leave Izembek Lagoon within about 12 h, usually at night.

Black brants arrive in winter habitats in Baja California within 60−95 h of departure from Izembek Lagoon. <where numbers can reach 130,000>31 They metabolize nearly one-third of their body mass during the 2,600 nautical mile flight across the Pacific Ocean to San Quintin Bay, Baja California, Mexico."32 This means that the brant fly non-stop for about 75 hours at an average speed of 35 nmph!

Black brant are hunted by local people as they stop over at St. Catherine Cove on Unimak Island in the fall to feed before their southern migration.

Common Teal: Anas crecca

Anas crecca nim'iaAleut names: "Attu: Cheerrh-ooli (obviously the Russian name)

Atka: Krech-cheer-tha (derivation from Russian is at least suggested by the middle syllable)

Ataxciyax (Jochelson — probably the true Aleut name)

Russian, Commander Islands: Tschirok (Stejneger)It is now well established that the breeding species of teal throughout the Aleutian chain is Anas crecca. During our expeditions, with only one exception, when a close view of males was possible, or when specimens were collected,- the bird proved to be the common teal. Beals and Longworth collected a male at Unimak Island, June 11, 1941. This is the easternmost point for which we have a record of this bird... These teals are the most abundant fresh-water ducks in the Aleutians."

Murie's full account of the Teal can be seen here.

Mallard: Anas platyrhynchos:

Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchosAleut names: "Attu: Argh'-ich

Atka: Ag-ich (apparently the same word in both dialects)

Russian, Commander Islands: Selesenn (Stejneger)""The mallard is widespread throughout the length of the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands, both as a breeding species and as a winter resident. ... In 1886, Turner reported that the mallard was plentiful in the Aleutians in winter, and stated that it breeds sparingly on Agattu and Semichi Islands and that a few pairs were seen on Amchitka Island in the latter part of May 1881 — which indicates nesting. Our expeditions verify this information. In1936, Attu natives stated that they had observed these birds nesting near streams, and stated that they winter there. "9

Murie's complete mallard description can be read here.

Harlequin Duck: Histrionicus histrionicusLocal name: Rock Duck

Aleut names:" Attu : Kagh'-i-ach

Atka: Kagh'-a-thi-ga

Unalaska : Kang-a-rich

Unimak: Kang-ath'-a-gich

Russian, Commander Islands: Kamenuschka (Stejneger)""This is the most abundant duck in the Aleutian Islands. We found harlequin ducks at practically every island that we visited, singly sometimes, generally in small groups, and occasionally in larger flocks. It is safe to say that, at one time or another, harlequin ducks occur at every island, large or small, from Unimak to Attu. Stejneger has reported them to be common in the Commander Islands.

They were also found east of the Aleutians— at Amak Island, at Izembek Bay, and at False Pass."9

The complete entry for Harlequins by Murie is here.

Red-Breasted Merganser: Mergus serratorAleut names: "Attu: Criich-ah'-lich

Atka: A-ga-lai-ahh

Agldyax (given by Jochelson as applying to two species)

Russian, Commander Islands: Krakhal (Stejneger) (The Attu name is undoubtedly a corruption of the Russian.)This is the commoner merganser of the Aleutian district....

In 1925, I found this merganser nesting about Izembek Bay, and, on May 25, 1925, 4 were seen on a mountain stream below Aghileen Pinnacles. (On May 4, and on several subsequent days, red-breasted mergansers were noted at Urilia Bay, on Unimak Island.)Chase Littlejohn, in 1887-88, said that this duck breeds at Sanak and at Morzhovoi Bay, where they remained all winter."9

Murie's account of both merganser species is here.

Willow Ptarmigan: Lagopus lagopus"Aleut: Alladek (Wetmore)

The willow ptarmigan, distributed throughout the Alaska Peninsula, is represented by two races, L. 1. alascensis and L. I. muriei. Gabrielson and Lincoln (1949) referred the subspecies on the Alaska Peninsula proper to alascensis, as distinct from the races on nearby islands."

"Beals and Longworth (field report, 1941) reported numerous ptarmigans on Unimak from February 26 to April 10, in flocks of 25 to 300 birds. They noted, on March 6, at False Pass as follows: "Large flocks of 300 or more birds each flew about the alders back of the cannery. We saw several flocks of 75 to 100 birds in Sourdough Flats and vicinity the same day." On March 24, they reported "ptarmigan by the hundreds" in the valley back of False Pass."9

Murie's account of the ptarmigan is here.

Black-Billed Magpie: Pica pica

Pica pica hudsonia

"Turner and Nelson both reported the magpie as common on Kodiak Island, and Friedmann (1935) has listed many specimens taken there. In 1940, Cahalane observed several on Kodiak Island and found them in many places in the Katmai region. We noted magpie feathers at Port Chatham, Kenai Peninsula, in 1936. On May 10, 1936, we saw a magpie on Ushagat, Barren Islands; on May 13, we saw one on Afognak; on May 16, we saw several birds and a nest with eight eggs on Nagai Island, Shumagins; and, on August 26, we saw several at Sand Point, Popof Island, in the Shumagins. We also noted one on Dolgoi Island, May 24, 1937. In 1940, Gabrielson observed the magpie at Kodiak, Sand Point (in the Shumagins), and Brooks Lake. Turner (1886) heard of its presence at Belkofski, and he saw one on Unga, in the Shumagins. Gianini (1917) found magpies and nests at Stepovak Bay, and Wetmore found them nesting at King Cove and saw them at Belkofski.

Dall had stated (1873) that magpies do not occur on the north side of Alaska Peninsula, but, in 1925, I found them nesting at Moffet Cove, Izembek Bay. Undoubtedly, magpies are more plentiful on the Pacific side.

Curiously enough, we did not find any on Unimak Island, and local residents said that they do not occur there, nor on other Aleutian Islands. "9

Magpies first appeared in False Pass, Unimak Island, around 1970. They are now numerous. Magpies were the culprits in raiding bank swallow nests on a high sand bank above the beach just south of Whirl Point, Unimak Island in the summer of 2009. They clawed their way into the nests and destroyed them such that all the swallows abandoned the bank. Magpies often get trapped in stored crab pots when they enter to check out the old bait smells and then cannot find their way out. Their large stick nests are located in several old sika spruce trees in the village as well as in alder brush along the valley.

Bald Eagle: Haliaeetus leucocephalus

Haliaeetus leucocephalus alascanusAleut names: Attu: Tirrgh-luch

Atka : Tig-a-lach

A-waich'-rich (immature)

Alaska Peninsula: Tikh-lukh (Wetmore)The bald eagle is commonly distributed throughout the length of Alaska Peninsula and adjacent island groups, and the Aleutian chain. It is numerous in some places. In the Aleutians, nearly every island that we visited had at least 1, often 2 or more, pairs, nesting. They are numerous about the larger islands. Williams noted 15 eagles in Bay of Islands, Adak Island, July 2, 1936, and more were found on other parts of the island. On June 29, we saw several at Kanaga Island. The caretaker of a fox- ranching establishment there had killed 14 of these eagles for the bounty, and he planned on raiding 20 more nests later.

For some reason, the bald eagle is scarce in the Near Islands- including Attu, Agattu, and Semichi. We observed a single pair on Agattu in 1937, but we saw none at Attu or Semichi and the natives assured us they were very scarce. However, we found a nest on Buldir Island, and from that point eastward bald eagles were common.

Not only do eagles occur along the Alaska Peninsula, they also occur on the offshore island groups. In 1940, Gabrielson observed them in several places at the base of Alaska Peninsula. At Kodiak, in 1936, one merchant erected a sign advertising the fact that eagle feet were acceptable as cash (bounty could be collected for them).

"The first-year plumage is dark ; as Bent says, "uniformly dark 'bone-brown' to 'clove brown' above and below; the flight feathers are nearly black, but there is usually a slight sprinkling of grayish white in the tail." In the first year, both the bill and cere are of a blackish-slate color. The iris is brown, and the pupil is black. At this stage, the eyelids are still plumbeous."

"A later phase, which possibly may represent the third year, still includes the dark bill, with a dull-yellowish hue appearing on the lower mandible and the margin of the cere. The eye is dull yellow also, and a yellowish tinge is encroaching upon the preocular area. The eyelid is gray, and the gape is yellow. There is much light speckling on the head, though the head is chiefly brownish. The specimen on which this description is based did not have the light mottling on upper parts falling into a pattern of three light patches, as was seen on many birds; instead, it was more scattered.

In still another phase, which is quite advanced, the head is white, speckled with a blackish hue. The beak is a dull-yellowish one — perhaps best designated as tan, somewhat streaked with a slaty tone. The lower mandible is bright yellow at the base. The cere is a mixture of gray black and yellow. The eye is yeJlow (as in the adult), the eyelid is a brighter yellow, the preocular area is pale yellow, and the gape is a rich, bright yellow."9

The complete Bald Eagle text by Murie is here.

Land Mammals of Unimak Area:

Ursus arctos gyas (Alaska Peninsula subspecies)

Aleut name: Alaska Peninsula: Tunarokh and Chuchiuk (Wetmore)

Tanghakh or Tanghaghikh (Geoghegan)9"Apparently, some residents of Unimak Island had little fear of the brown bear. Arthur Neumann related that on one occasion he had forced a group of bears into the rough water of Swanson Lagoon on a stormy day to watch them struggle in the choppy waves. "

"The Alaska brown bear deserves respect and should be approached carefully, because it can cause considerable damage for a few moments even after being shot through the heart. It is best to realize that although this bear is not particularly vicious, it is very curious and is likely to investigate anything unusual. The bear's eyesight is not good, which may account for its close approach at times."....."When the salmon ascend the streams in June, the bears seem to subsist largely on salmon. However, they do not entirely forsake the highlands. Long trails leading back to the highlands show the routes of travel down to the salmon streams, though the bears often sleep near the streams, in the alder thickets. The bears scoop out beds along the banks, and sometimes pile up moss and other vegetation to form a mattress. We found one such structure at Izembek Bay, and, in 1911, Wetmore described a similar heap found at Morzhovoi Bay, at a salmon pool: "On the bank above this was a curious bed of moss and grass dug up from the ground around piled up a foot deep and twelve feet square. Below it were smaller ones freshly made about two feet square and all padded down as though bruin had been sitting on them."9

Click here to read Murie's full account of the Brown Bear.

A bear video done by an amateur (author unknown) is available for viewing here.

"Aleut name: Atka: Itkayech (Saur)

Unalaska: Ithayok (Saur)

Morzhovoi Bay: Ikthinkh (Wetmore)""Jochelson (1925, p. 36) found a "reindeer" antler spoon in a village midden on Umnak Island. This spoon, or the antler, may possibly have come from Unimak Island in trade."

"The field reports and conversations of Donald Stevenson, fur warden in the Aleutians from 1920 to 1925, revealed great fluctuations in the numbers of caribou on Unimak Island. In the early eighties and nineties, there was much caribou hunting by sea otter hunters, with the result that caribou were greatly reduced in numbers about 1894. When only a few hundred remained, hunting decreased and, as caribou were more plentiful on the peninsula at that time, annual migrations brought an influx of new stock which raised the herd to "full carrying capacity" of the island by 1905. "9

"Caribou were numerous on Unimak Island during the early 1900s, and they probably reached a population high of at least 7,000 in 1925 (Murie 1959). By the 1940s, caribou had declined, and during the first aerial survey of Unimak Island in November 1949, no caribou were observed (Skoog, 1968). In a 1953 survey, again no caribou were found on Unimak, but by 1960, almost 1,000 were present (Skoog 1968). In 1975, Irvine (1976) counted 3,334 caribou and estimated there were about 5,000 on the island. After the mid-1970s the population declined, and during most of the 1980s and early 1990s only about 300 caribou could be found. The current population decline was preceded by a slight increase during the early 2000s. In 2000, a hunting guide counted 981 caribou and estimated a population of at least 1,100 on the island (Schuh, pers. comm.)"11

For the complete Murie account of caribou, click here.

The caribou herd on Unimak Island has declined markedly in recent years such that no subsistence hunting is allowed to the local residents. The Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game has proposed methods to control the wolf population to give the caribou a chance to recover their numbers but the USFWS has not as yet allowed the work to be done on Refuge land. As of April, 2011, no effective solution to the declining caribou population has been agreed upon. Please see these reports for more information: USFWS Environmental Assessment, Dec. 2010 and a news report from APRN.

Red Fox: Vulpes (fulva) vulpes"Aleut name: Morzhovoi Bay: Ikowukh (Wetmore)

From vocabulary compiled by R. H. Geoghegan at Valdez in 1903: Ukhaching

Russian: Lee-see-sha (Buxton)

Russian, Siberia; See-way-doos-ka (cross fox)""The red fox is plentiful throughout the Alaska Peninsula and is found on the eastern Aleutian Islands. Unimak Island, in particular, has a large fox population, and the species occurs also on Akun, Unalaska, Umnak, Chuginadak, Amlia, Adak, Kanaga, and Sanak Islands. Foxes occur on Dolgoi, which was utilized for commercial fox propagation — it is possible that the fox originated here in that fashion. Great Sitkin, also, was said to have had some red foxes. Those on Amlia and Adak Islands are the silver-gray color phase."

"It is probable that the dark color phases occurred also on Alaska Peninsula, and it is almost certain that excessive killing of these darker kinds, on a selective basis because of their greater value, has served to bring the population back to a practically uniform type, the red phase. The silver fox persists on Amlia Island, but this island has been leased and the foxes are controlled artificially. We can no longer find the dark kinds in any numbers on Unalaska, where they were first found."9

Foxes were trapped by the Aleuts for subsistence use in the Unimak area for thousands of years. With the arrival of the Russians after 1742, the commercial fox pelt trade began and continued after the Americans bought Alaska in 1867. Fox trapping was done extensively on Unimak until the fur market crashed around 1940. Trapping cabins were built at many remote locations on the island and on the Alaska Peninsula. Unimak Island was divided into "trapping areas" that were licensed to individual trappers. The local communities of Morzhovoi, False Pass and Ikatan depended on fox trapping for a livelihood. See more details about trapping on Unimak on this website here.

For the complete Murie article on Red Fox, click here.

Weasel: Mustela erminea

"Mustela erminea arcticaAleut name (dialect?) : Samikakh (Geoghegan)

Aleut Iliamna Village: Ameetahduk (Osgood)

Indian, Iliamna Village: Tahkiak and Kahoolcheenah (Osgood)

Russian: Gor-no-stai-e (Buxton)Hall (1951) has placed the weasels in three groups: The least weasels, rixosa; the long-tailed weasels, frermta; and the short- tailed weasels, erminea. Accordingly, the weasel of Alaska Peninsula becomes Mustela erminea arctica.

These weasels occur throughout the entire length of the Alaska Peninsula and Unimak Island, as well as the Kodiak-Afognak group. They are common on Unimak Island but have not been found on any islands farther west."9

For full description of the weasels by Murie, click here.

Land Otter: Lutra canadensis

"Lutra canadensis yukonenslsAleut name: Ahkweeah (Osgood) Morzhovoi Bay: akhuyakh (Geoghegan)

Aleut, Ahkwenkh (Wetmore)

Russian: Nee-drah (Buxton)This mustelid species ranges throughout the length of Alaska Peninsula and Unimak Island, but we have no records farther west. Wetmore reported that they were partial to salt water as well as fresh, ''frequently swimming boldly out to the islands, lying off the coast."

In 1925, I learned that a local trapper had caught 10 otters at Urilia Bay in the winter of 1924-25."9

These land otters are common along Isanotski Strait and usually travel in family groups. They often make their resting areas under old abandoned buildings. Their "fun slides" can often be found on banks, with tell-tale matted-down grass and sign. They are usually very curious upon seeing people walking on the beach and if there is a dog, they may tease them by chirping and bobbing up and down.

Sea Mammals of Unimak Area:

Sea Otter: Enhydra lutris lutris

"Aleut names: Attu: Chach-toch

Caxtux (Jochelson)

Atka : Ching-d-tho

Cna-tux (Jochelson)

Morzhovoi Bay (dialect?) : Chngatukh (geoghegan);

Chgatluk (Wetmore)

Base of Alaska Peninsula: Ahchgh-nahchgh (Osgood)

Kodiak: Ach-an-ah (King)

Kwakiutl Indian: Kas-uh (Dawson)

Russian: Bohr Morskoi (Steller), "sea beaver"

Bobry, adult males

Matka, females

Koschloki, 1-year-olds

Medviedki, "little bears" — cubs""The sea otter spends most of its time in the water. When wishing to sleep, it simply lies on its back and dozes, sometimes with a strand or two of kelp across the body serving as an anchor, whether intentional or not. When feeding, the animal dives for its food, then lies on its back to eat, using its chest for a table. On specimens from Alaska that were examined, the hair on the chest was somewhat worn, no doubt through this use in feeding. When the little pup wishes to sleep, it curls up on the mother's abdomen, and both mother and offspring lie quiescent on the water. The offspring also climbs aboard the mother to nurse.

When startled, the mother puts an arm around the little one and dives with it. On some occasions, the mother seemed to pat the little one on the head first, as if by this patting or pushing motion she were warning it of the impending immersion. This was never clearly seen, however, and it needs to be verified. If merely worried or suspicious, the mother seizes the pup with her arm and swims away with it."

"The sea otter does come ashore, however, and there are favorite hauling-out places for certain individuals. One or more mothers may climb out on a kelp-covered rock, with their youngsters, where they squirm about and fondle their little ones and end- lessly dress their fur. Sometimes a pup will wander off to the water, or will be reluctant to climb out on the rock. Then the mother persistently forces him, nudging and pushing, until he complies with her desire to haul out on the rocks. Occasionally, a male will join the group. We also saw lone individuals, apparently adult males, curled up on a rock, where they may lie long enough for the fur to dry. Even here, they appear restless, and may raise their heads to look about, yawn, rub their faces with their paws, or otherwise dress their fur. It is reported that sea otters go ashore in times of severe storms, but that sometimes they succumb in heavy surf on the reefs. "

"It is well established that the northern sea otter feeds largely on sea urchins, and that this diet is supplemented by considerable quantities of mollusks, including mussels, chitons, limpets, snails, and others; and with lesser quantities of crabs, octopuses, and other items — fish play a minor role in the diet. More detailed analyses of the diet of the northern sea otter are given by Williams (1938), Barabash-Nikiforov (1935), and Murie (1940)."9

Read Murie's full account of the sea otter, here.

Bob "Sea Otter" Jones (USFWS) is famous for working to save the Aleutian Cackling Goose, but he also helped reintroduce sea otters to the eastern Aleutians from Amchitka. Read an interview with Bob Jones here.

Sea otters have again returned to the Unimak area where they were once abundant. By the early 1980's rafts of about 50 otters could be seen in Isanotski Strait and Ikatan Bay. Since then, their numbers have declined significantly. Other areas in the Aleutians, are suffering a sharp decline in local otter populations. One study suggests that Orcas are responsible: "After nearly a century of recovery from overhunting, sea otter populations are in abrupt decline over large areas of western Alaska. Increased killer whale predation is the likely cause of these declines. Elevated sea urchin density and the consequent deforestation of kelp beds in the nearshore community demonstrate that the otter's keystone role has been reduced or eliminated. This chain of interactions was probably initiated by anthropogenic changes in the offshore oceanic ecosystem."16

Kelp Forests in the Aleutian Ecosystem:

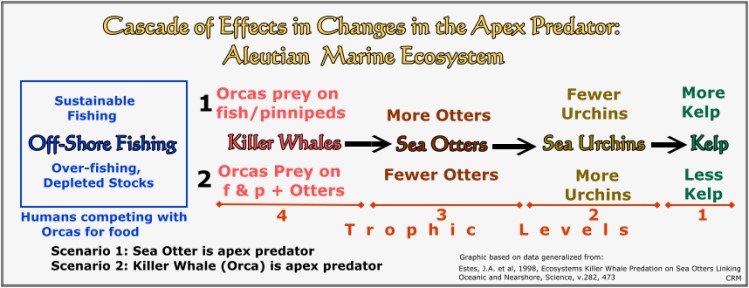

The Sea Otter-Sea Urchin-Kelp interrelationship in fundmentally important in maintaining "kelp forests" in the Aleutian marine ecosystem. If the sea otter population is high, they prey heavily on sea urchins and this keeps the urchin population down. Since the urchins are kelp-grazers, kelp forests can then grow along the coastline. These kelp forests are important because they provide a rich and varied habitat for various kelps plus numerous fishes, starfish and other invertebrates and even some birds.19 It is interesting to note that it appears that the early Aleut/Unangan people sometimes over-exploited the sea otter population with many ramifications.10There is a cascade of effects in the food web when changes are made to the position of the "apex predator" in the food chain, as shown in the graphic below. Trophic level 1 (kelp) is the "autotroph" or the producer in the food chain, producing plant material from sunlight and nutrients upon which the higher trophic levels depend. Level 2 (urchin) is a heterotroph consumer-grazer, eating autotroph kelp products. Level 3 (otter) is a heterotroph consumer-carnivore, eating other animals (urchins). Level 4 (killer whale-orca) is a heterotroph consumer-carnivore eating fish and pinnipeds and, if necessary, sea otters. Orcas do not usually hunt sea otters and therefore are not usually part of this particular food chain. Humans are omnivores and compete with the orca for food (commercial off-shore fishing), forcing the orca into the top predator position, thereby creating a cascading chain of effects in the food web.19

When the sea otters decrease in numbers because of human or orca predation, the number of sea urchins grows rapidly, often turning the sea floor into kelp-less barrens.18 When sea otters increase in numbers, the sea urchins diminish in numbers and the kelp forest habitat returns. It now appears that intensive off-shore commercial fishing is competing with the orcas for the same food. Low fish stocks have caused a steep decline in pinniped populations (harbor seals, fur seals & sea lions) and this has deprived the orcas (killer whales) of their traditional fish and pinniped prey. So the orcas now target the sea otters, pushing down the sea otter population causing a cascade of effects.16 The complexity of the food web in the North Pacific littoral zone is now beginning to be understood in more detail.19

Killer Whale (Orca): Orcinus orca

"(Grampus rectipinna)Aleut names: Attu: A'-ga-ghi-ach

Atka: Ah-ga-loh

Ah'-ga-luch

Aleut (dialect?) : Ag-lyuk (Turner)The killer whale is common along Alaska Peninsula and throughout the Aleutians. We found a dead one on Agattu Island. We generally saw them in small groups, or alone, but as many as 25 in a school were recorded. The most common number for a group was three. Ernest P. Walker (unpublished notes) has recorded some large schools of killer whales. On September 16, 1913, in Icy Straits, he saw a school of 500 or more; on July 19, 1915, near Port Armstrong he saw another school of about 300. He quotes Captain Louis L. Lowe to the effect that he had seen schools of 400 to 1,500 off the southwestern end of Kodiak Island, and, in April 1922, he saw a school of about 1,000 off Ugak Island near the Kodiak coast. "They were apparently headed northward and were no doubt keeping close company with the fur seals."

"Again, Walker says — Captain Haynes says that on only one occasion has he seen a large school of killers or thrashers. This was early in June near Unimak Island, where he encountered a remarkable assemblage of various whales, seals, and other life feeding and many killers were present. There was a great deal of fighting accompanied by leaping."

" We frequently found killer whales cruising along the borders of kelp beds. On one occasion, a killer passed directly under our dory — a rather disconcerting experience. We obtained no direct evidence of their food habits, but Turner saw a killer whale kill a nearly full-grown sea lion at Bogoslof Island, and, at Tigalda Island, he watched two killers attacking a large finback whale. He had also seen them following schools of smelt, which suggests a diet including fish."9Click here to see full Orca account by Murie.

Steller Sea Lion: Eumetopias jubata"Aleut names: Attu: Kdv-rch

Atka: Kow'-uhh

Aleut (dialect?) : Qa'hwax (Jochelson)

Khawakh (Geoghegan)

Russian: Sivutcha (Steller)Sea lions are found throughout all of southwestern Alaska, extending to Attu Island, where we saw some at its westernmost point, Cape Wrangell. There were colonies, numbering from 40 or 50 to several hundred individuals, at such places as Amak Island, Bogoslof (the outstanding herd),Carlisle, Yunaska, Chagulak, Amukta, Segula, Semisopochnoi, Ilak, and Buldir. Bogoslof has by far the largest and most spectacular herd — so outstanding that it deserves special consideration as an object of particular scientific, as well as popular, interest. In 1938, Scheffer estimated 800 sea lions were on Bogoslof.

The Aleuts use the skin of the sea lion for leather, and find the flesh very palatable. On one occasion, I ate the flesh of a young sea lion and found that it was decidedly acceptable."9

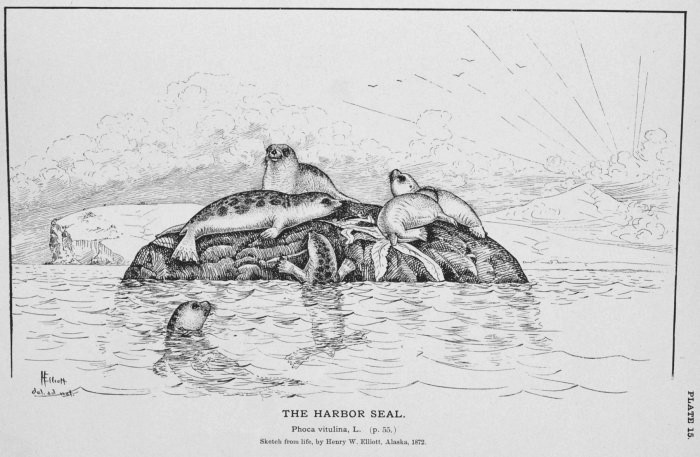

Harbor Seal (Hair Seal): Phoca vltulina

Phoca vitulina richardiiLocal name: Hair Seal

"Aleut names: Attu: Ish'-u-gich

Atka: Ish'-u

Aleut (dialect?) : Isv.kh (Geoghegan)

Hisook (Wetmore, at Morzhovoi Bay)

Ishooik (Osgood).

Russian, Siberia (Gichiga) : Ola (Buxton)

Russian, lkhotsk, Ayan, Pengina, and Marcova: Largha (Buxton)""Among the Aleutian Islands, seals were usually found in the kelp beds, but they do not always seek such a habitat. I had a fine opportunity to study these animals in the spring and summer of 1925, at Unimak Island and at the west end of Alaska Peninsula. They were very common at that time. They hauled out on the boulders of the reef at Amagat Island and basked on the kelp-covered boulders near the beaches of Amak Island. In Urilia Bay, they hauled out on the sand along the entrance to Rosenberg Lagoon, and in Izembek Bay they hauled out on shoals and sandbars at low tide. A small sand island in the channel between Operl and Neumann Islands was a favorite hauling-out place.

Seals pick a resting place that provides ready escape, always near deep water. If the ebbing tide recedes from a boulder on which a seal is resting, the animal will move to another rock, nearer to deeper water. When navigating the shallow Izembek Bay with our whaleboat, we could steer a deep-water course by noting the location of resting seals.

Mothers and pups appear to be very affectionate, swimming near each other and occasionally touching noses. A little one would try to climb to its mother's perch on a rock. After a while, the mother might lazily roll into the water to join it; later, both might be able to clamber out on the same perch."

"As one would expect, the seal was much prized by the Aleuts, and was used for food and for other purposes. Wetmore, writing of Unalaska and neighboring islands in 1911, stated that "The hide is used for various purposes and oil is tried out of the blubber. The gut is split and dried and used for many purposes. It is sold in the store like cloth at about 15 cents a yard.""9

The complete text on the harbor seal by Murie can be read here.

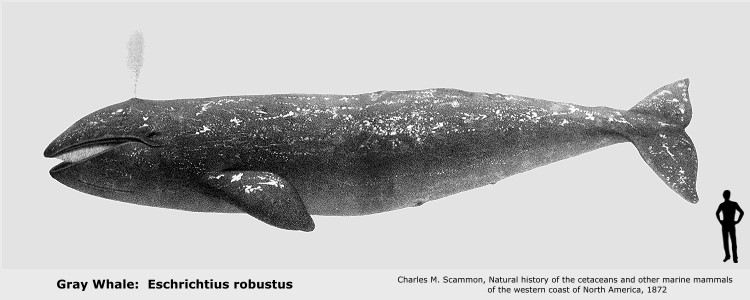

Gray Whale: Eschrichtius robustus

"Gray whales are mysticetes, or baleen whales. Gray whales are the only species in the family Eschrichtiidae. These large whales can grow to about 50 ft (15 m) long, and weigh approximately 80,000 lb (35,000 kg). Females are slightly larger than males. They have a mottled gray body, with small eyes located just above the corners of the mouth. Their "pectoral fins" (flippers) are broad, paddle-shaped, and pointed at the tips. Lacking a dorsal fin, they instead have a "dorsal hump" located about two-thirds of the way back on the body, and a series of 8-14 small bumps, known as "knuckles," between the dorsal hump and the tail flukes. The tail flukes are more than 15 ft (3 m) wide, have S-shaped trailing edges, and a deep median notch. Calves are born dark gray and lighten as they age to brownish-gray or light gray. All gray whales are mottled with lighter patches, and have barnacles and whale lice on their bodies, with higher concentrations found on the head and tail."....

"Most of the Eastern North Pacific stock spends the summer feeding in the northern Bering and Chukchi Seas, but gray whales have also been reported feeding along the Pacific coast during the summer, in waters off of southeast Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. In the fall, gray whales migrate from their summer feeding grounds, heading south along the coast of North America to spend the winter in their breeding and calving areas off the coast of Baja California, Mexico. Calves are born in shallow lagoons and bays from early January to mid-February. From mid-February to May, the Eastern North Pacific stock of gray whales can be seen migrating northward with newborn calves along the West Coast of the U.S."21

Gray Whales are hunted intensively by killer whales in the Isanotski Strait area. Gray Whales in the Unimak area often show up in early May each year on their northward migration from Baja California. They may spend several months in Isanotski Straits and the Ikatan Bay area. Orcas (killer whales) usually also show up at this time to prey upon the calves of the gray whale.

"Killer whales bite the grey whales' pectoral fins, holding them below the surface and even rolling onto their heads in an attempt to drown them. Others bite at the tissue around the throat rather than tackle the taut outer skin. "They tear through that loose baggy throat tissue and get into the tongue," Barrett-Lennard said. "It has the effect of killing the whale very quickly through loss of blood."

For researchers, finding the underwater kill sites is as easy as following their noses, as well as the slick created on the surface. Flocks of seabirds attracted to floating chunks of blubber are another clue. The sunken carcass then becomes a convenient refrigerator so perhaps 10 to 15 killer whales can return time and again over five or six days. But they are not the only predators to benefit. Some carcasses bloat up, float to the surface and drift onto the shoreline to be consumed by bald eagles, red foxes and hungry grizzly bears emerging from their dens."22

A February, 2011 newspaper article on the current Orca-Gray Whale situation can be accessed here.

References:

1) Wikipedia article on Sockeye Salmon, modified.

2) Wikipedia article on Coho Salmon, modified.

3) Wikipedia article on Chum Salmon, modified.

4) Wikipedia article on Pink Salmon, modified.

5) Wikipedia article on Chinook Salmon, modified.

6) ADFG: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=chumsalmon.main

7) ADFG: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=sockeyesalmon.main

8) ADFG: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=pinksalmon.main

9) Murie, Olaus J. (1959) FAUNA OF THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS AND ALASKA PENINSULA, 1936-38, U.S. Dept. Interior, Fish & Wildlife Service, Washington.

10) Simenstad, Charles A., James A. Estes, Karl W. Kenyon (1978), "Aleuts, Sea Otters, and Alternate Stable-State Communities", Science, vol 200, pgs 403-411

11) USFWS, (2010), "Management Alternatives for the Unimak Island Caribou Herd Environmental Assessment", Department of the Interior. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, In cooperation with State of Alaska Alaska Department of Fish and Game, December 2010, GAP Solutions, Inc. Washington, D.C. , pg. 4

12) http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Publications/ZooGoer/1999/6/alaskaotter.cfm

13) Source: Wikipedia: Chiton

14) Meyer, K.F., D.K. Hilliard, "Shellfish poisoning episode in False Pass", Alaska. N Engl J Med. 1953 Nov 19;249(21):843. Found at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2024527/

15) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paralytic_shellfish_poisoning

16) Estes, J.A. et al, 1998, Ecosystems Killer Whale Predation on Sea Otters Linking Oceanic and Nearshore, Science, v.282, p.473

17) Estes, J. A., Danner, E. M., Doak, D. F., Konar, B., Springer, A. M., Steinberg, P. D., Tinker, M. T. & Williams, T. M. 2004 Complex trophic interactions in kelp forest ecosystems. Bull. Mar. Sci. 74, 621–638.

18) Scheffer, Victor B., "Invertebrates & Fishes Collected in the Aleutians, 1936-38" in Murie, Olaus J. (1959), Fauna of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska Peninsula, Dept. of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

19) Estes, J.A., D.F. Doak, A.M. Springer and T.M. Williams, 2009, Declines in Southwest Alaska: a Food-web Perspective, Phil. Transactions Royal Society, Biological Sciences, 1647-1658.

20) Scammon, Charles M., 1872, Natural history of the cetaceans and other marine mammals of the western coast of North America, J.H. Carmany, San Francisco

21) http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/mammals/cetaceans/graywhale.htm

22) Article in Vancouver Sun, "Whale hunting orcas of False Pass"January 5, 2008: http://www.canada.com/cityguides/winnipeg/info/story.html?id=4ab95d2a-9bab-4124-84ef-54a9512859d0

23) http://www.thedutchharborfisherman.com/article/1107killer_whales_cache_their_catch

24) Best, E.A., 1977, Distrubition and Abundance of Juvenile Halibut in the Southeastern Bering Sea, IPHC, Seattle pg. 5

25) http://www.fakr.noaa.gov/ram/ifq.htm

26) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pacific_halibut

27) http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/fishwatch/species/pac_cod.htm

28) http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/fishwatch/species/pacific_halibut.htm

29) http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=commercialbyfisherygroundfish.main

30) http://www.fakr.noaa.gov/ (National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Region-NOAA)

31) http://izembek.fws.gov/wildlife.htm

32) Dirk V. Derksen, David H. Ward "Life History and Habitat Needs of the Black Brant", Waterfowl Management Handbook, USFWS, 1993, pg. 5