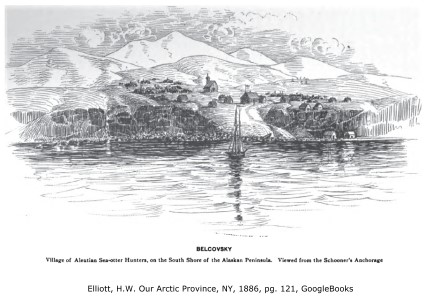

Belkofski, Village of Aleutian Sea-otter Hunters, in 18861

Click on drawing to see larger version.

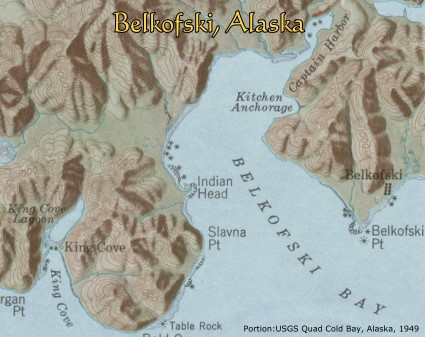

Belkofski is located on the south side of the Alaska Peninsula, facing the Gulf of Alaska. It was founded in 1824 by the Russian American Company by moving all the Aleuts from the Sanak Islands to this new location. The move was intended to protect the sea otter population on Sanak that was in serious decline. The community was finally abandoned in about 1990. Belkofski (Taxtama in Aleut) was originally subordinate, in the Russian American Company's administration, to the resident agent (baidarschik) at Unga and later the Belkofski parish became subordinate to Unalaska. Belkofski was linked to two other local Aleut villages, Morzhovoi and Pavlovskoe, both now abandoned.8

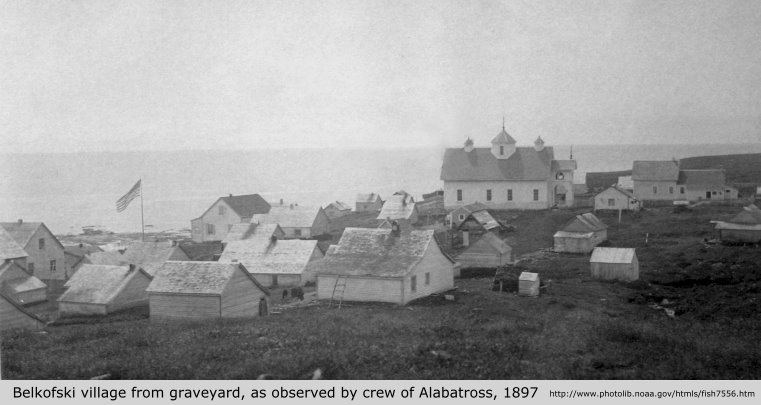

The first Russian Orthodox church in Belkofski was put up in 1843 and a new one was built in 1880. The interior of the Belkofski church in 1888 can be seen here. A school was established in 1901 and closed in 1976.6 The Belkofski community lands are now controlled by the Belkofski Corporation with its office in King Cove.5 A good detailed historical description of Belkofski can be seen in Lydia Black's book on the Aleutian's East Borough.3

<about 1880>"North of the Chernobura reef, on the mainland, is the village of Belkofsky. The settlement is situated on a bluff on the south slope of a mountain rising immediately behind it. There is no anchorage, only an open roadestead, from which vessels have been blown away with the loss of their anchors. Nearly all the houses of Belkofsky are neat frame cottages, erected for the natives by trading companies when sea otters were plentiful. They are generally painted in white and light colors, and are set off in pleasing contrast by the green mountain slope behind them. Even now, in its decadence, Belkovsky contains 185 people, among them a few white men, sea otter hunters, who make this their permanent home. Less than a decade since, the sea otter pelts collected at this station numbered in the thousands, and there were 3 rival stores bidding for the precious peltry, wheedling and coaxing the lucky hunter to sell his skins, then stimulating him to the most reckless extravagance, and finally hurrying him off again with an outfit given on credit to face the whistling gale and raging sea in search of more furs." ....

"In our days the glory of Belkofsky has departed, the number of otters secured has decreased from thousands to less than a hundred.... The rival stores stand vacant, and even the shelves of the only surviving business are but thinly stocked with inexpensive wares. Salmon and seal meat have once more assumed their place as staple food, and the luxuries of former days are but a pleasant memory.4

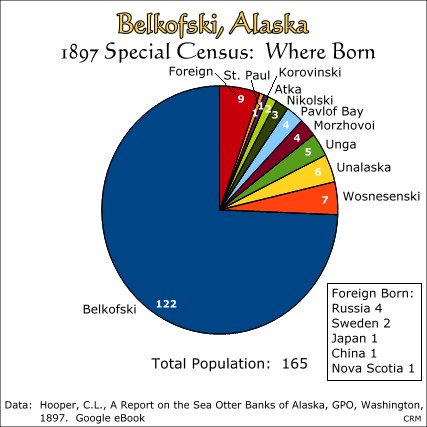

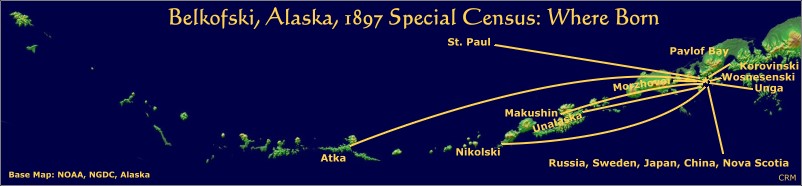

Belkofski in 1897 had a fairly large number of residents who were born elsewhere. This was due primarily to its importance as the center of sea otter hunting.

Belkofski was created by the Russians in 1824 when all the residents of Sanak Island were moved here, creating a new village.3 The Sanak area had always been the center of sea otter hunting and when the people on Sanak were required to relocate, they brought their skills and interests with them. Under the new American administration after 1867, it was logical that Belkofski would become an important sea otter harvesting center. Sea otter hunters came from many other Aleut villages to take part in this lucrative hunt. There were high financial returns from the sea otter trade and the community prospered and grew quickly.

"Of all articles held by the latter for exchange, the fur of the sea otters was by far the most important. Since these animals were abundant throughout the Aleutian region thirty years ago, and the furs were valued at from $300 to $1000 each, their hunters became relatively wealthy, and the little Aleut villages became abodes of comparative comfort. In the settlement of Belkofski, on the peninsula of Alaska, numbering 165 persons all told, I found in the Greek church a communion service of solid gold, and over the altar was a beautiful painting, — small in size, but exquisitely finished, — which had been bought in St. Petersburg for $250. When these articles were purchased, Belkofski was a centre for the sea otter chase. With wise government, this condition of prosperity might have continued indefinitely. But we have allowed the whole herd to be wasted....."2

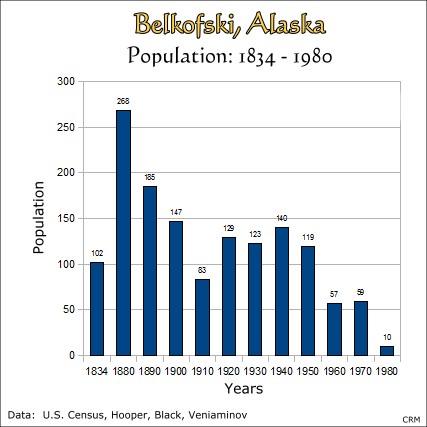

The Belkofski population graph shows the impact of changing economic and social pressures. In 1834, under the Russian administration, the community was reported as having 102 inhabitants. The next population count in 1880, after the American adminstation took over, the population increased by almost three times. This large influx of people, as shown above, came as the result of the rapid increase in sea otter hunting. As practiced under the American adminstration, the harvest of sea otters was basically uncontrolled, highly exploitative and unsustainable. The result was the local extermination of sea otters in this area of Alaska. The consequences for the people of Belkofski were dramatic with two-thirds of the population leaving the community by 1910.

"The people of Belkofski can now secure nothing which the world cares to buy. As they have no means of buying, the company has closed its trading-post, after a year or two of losses and charity. The people have become dependent on the dress and food of civilization. Suffering for want of sugar, flour, tobacco, and tea, which are now necessities, and having no way of securing material for boats, they are abjectly helpless. I was told in 1897 that the people of Wosnessenski Island were starving to death, and that Belkofski, the next to starve, had sent them a relief expedition. I have no information as to conditions in 1898, but certainly starvation is imminent in all the various settlements dependent on the company's store and on the sea otter."2

After the sea otter boom was over, the main occupations became the trapping of fox, bear, wolf and land otter for fur and commercial fishing for cod and salmon. In the late 1930's codfishing went bust. However, in 1913, a salmon cannery was built in King Cove, a community a short distance away, which provided a stable source of employment. Little by little, people from Belkofski moved away, to King Cove and other communities until in 1980 there were only 10 residents remaining. The village was abandoned around 1990.3

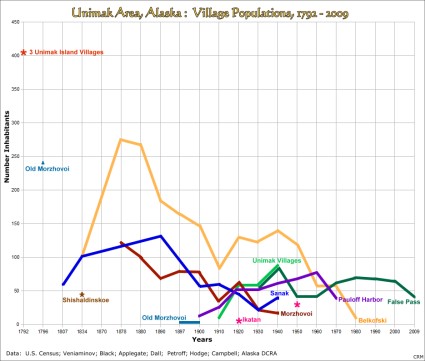

The population history of Belkofski is closely intertwined with the other communities in the area. Detailed population data for Aleut villages during the early Russian occupation of the area is not available, but it is well known that there were massive relocations of Aleuts and consolidation of villages. In the Unimak area, these relocations resulted in increased size and stability of three villages, Morzhovoi, Sanak and later, Belkofski.

Under the Russian administration, all three villages were engaged in the hunting of sea otters, the trapping of land fur animals and the harvesting of walrus ivory for the Russian American Company.3 Because of the over-exploitation of sea otters around the Sanak Islands, the Russians moved the Sanak Aleuts to the Alaska Peninsula and created Belkofski in 1824. But, as soon as the Americans took over the administration of the area in 1867, Sanak village was re-settled and the Sanak islands and reefs and the islands near Belkofski became the center of the sea otter trade. When the sea otters were over-exploited, the business collapsed by 1910 with strong negative impact on the population of all three Aleut communities as seen in the graph to the right.

After the building of the King Cove salmon cannery in 1913, Belkofski became more dependent upon work associated with the salmon fishery. During Belkofski's waning years, many of the villagers emmigrated to King Cove and the village was completely abandoned about 1990.

Click on graph to see larger version.

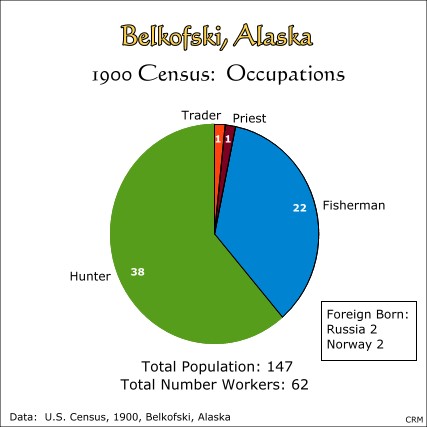

The 1900 census for Belkofski shows the heavy involvement of local men in the hunting of sea otters. It also shows that the sea otters were already being decimated and local people switched to work in the commercial fisheries. At this time, there were two cod fisheries in the area. The first was the codfish stations in Sanak and Shumagin Islands and local men may have found work there. The second cod fishery was on schooners that fished in this area and in the Bering Sea. Another fishery was developing at the time. It was the salting of salmon and it occured at Thin Point, about 15 miles to the west. No details are available, however, about the involvement of Belkofski people in these occupations.

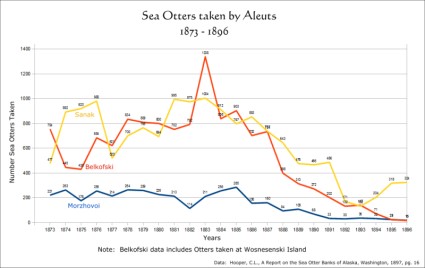

The sea otter harvest graph below shows the rapid decline of the sea otter harvest in this area.

Click on graph to see larger version.

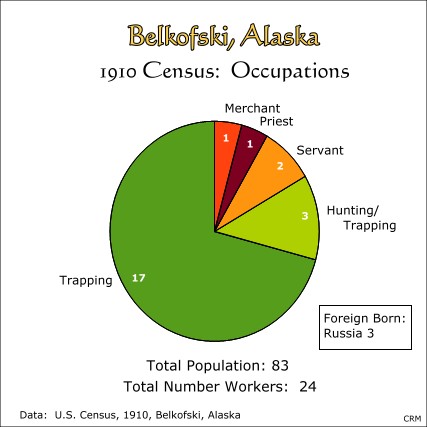

By the 1910 census, the hunting of sea otters had ended. Under the Russian administration, there was a well developed business with furs from land animals common in the area. Therefore, it was logical that local men would take up trapping. The Alaska Peninsula and some of the larger nearby islands have a number of fur-bearing animals and the Belkofski people depended upon them for their primary livelihood. Furs were still in high demand all around the world in cold climates, so that trapping was a fairly lucrative business. Bears, wolves, wolverines, land otter, mink and fox were trapped for their furs. Some local men were guides for hunting bear and Belkofski people often hunted bear in the spring for meat. The photo below shows a typical bear hunting camp.7

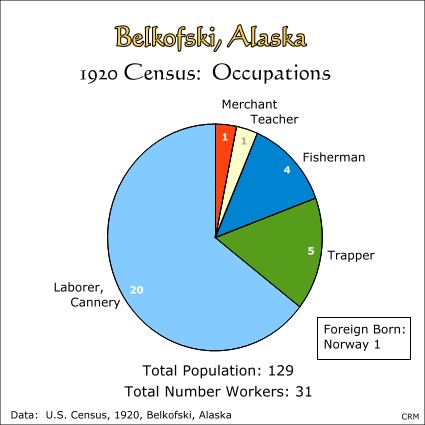

Belkofski at the 1920 census shows a major shift towards the commercial fisheries. The salmon cannery at King Cove attracted many workers and some of the Belkofski men became commercial fishermen themselves. Trapping was still important for some of the local men.

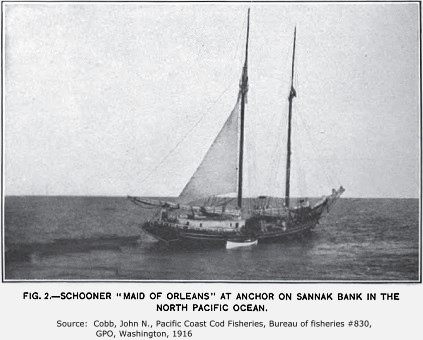

The photo below shows one of the codfish schooners that fished the Sanak and Belkofski area. Since local men were good dorymen and fishermen, these schooners would sometimes take on men from the villages for crew.9

See historical photo of King Cove Cannery here.

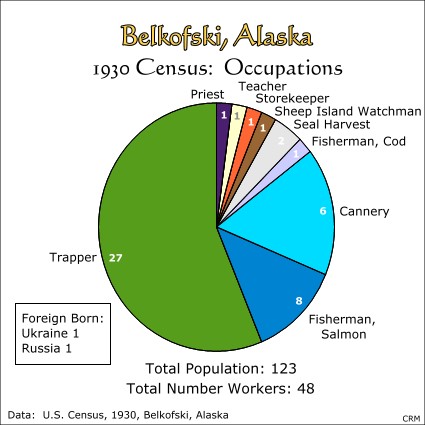

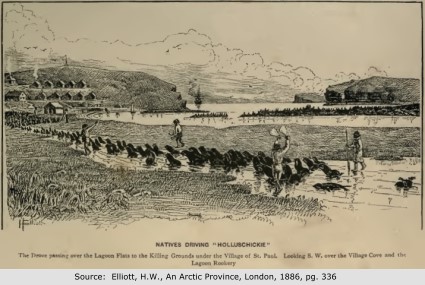

Belkofski at the 1930 census shows that a number of different occupations were now available. Traditional trapping of fur-bearing animals was still very important to the economy. Commercial salmon fishing and cannery work was also very important. The census shows more detail than in previous censuses and we see that there was one cod fisherman and one watchman at an island with sheep. Two men were employed at St. Paul, Pribilof Islands, helping with the seal harvest. The seal drive is shown below in an 1886 sketch.

The priest during this period was Father Dmitry Hotovisky, who was listed as a fisherman because he made most of his income from commercial salmon fishing. His wife, Antoinette, was the storekeeper. See Lydia Black's book for more information on Father Hotovisky, page 94.3

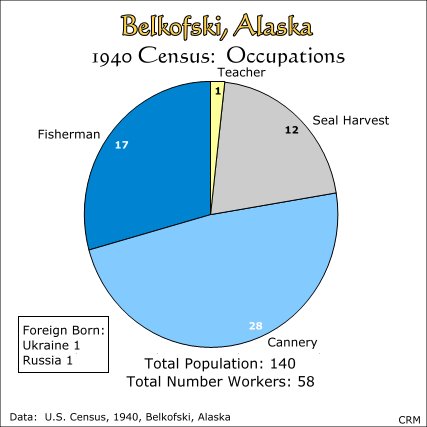

The 1940 U.S. census for Belkofski shows a shift away from trapping as the primary source of work. The fur market had collapsed in the late 1930's and did not recover. But, the salmon industry continued to prosper and since King Cove was nearby, many Belkofski workers spent the salmon season working at the Pacific American Fisheries salmon cannery there. During this time, many Belkofski men also worked as commercial salmon fishermen and delivered their catch to King Cove.It is interesting to note that twelve workers left Belkofski to travel to the Pribilof Islands to work in the harvest of fur seals. At this time the seal harvest was still relatively healthy and was controlled by the U.S. government.

There is no occupation listed as Priest, but Father Hotovisky is still on the enumeration sheet listed as a fisherman. Belkofski did have a school with a single school teacher.

Detailed population data for Belkofski is not available after 1940. Little by little the population of Belkofski dwindled until it was finally abandoned about 1990. Many former Belkofski residents now reside in King Cove.

After the creation of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971, the Belkofski Corporation was formed and currently has its office in King Cove: Belkofski Corporation, P.O. Box 46, King Cove, AK 99612, phone 907-497-3122.

References:

1) Elliott, Henry W., Our Arctic Province, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1886, pg. 121; Google eBook

2) Hubert, Philip Gengembre "Colonial Lessons of Alaska", The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 82, 1898; Google eBook

3) Black, Lydia T., History and Ethnohistory of the Aleutians East Borough, Limestone Press, 1999. p. 95

4) Report on the Population and Resources of Alaska at the 11th Census, 1880, Census Office, GPO, 1893, p.87 Google eBook

5) Belkofski Corporation, P.O. Box 46, King Cove, AK 99612, (907) 497-3122, Fax (907) 497-3123

6) Black, ibid, p. 91

7) Personal communication, Lorraine Jonsson, 2010. Bear photo in public domain: http://www.fws.gov/digitalmedia/ #FWS-5120

8) Black, ibid, p. 80

9) Cobb, John N. "Pacific Coast Cod Fisheries", Bureau of Fisheries # 830, GPO, Washington, 1916. Google ebook