The Unangan people were called "Aleut" by the Russians and that name became the name used almost universally in western languages, even though it was not the name these people used for themselves. The name, "Unangan", originally referred to the native people of the Eastern Aleutians, but is now often used to refer to all the people indigenous to the Aleutian Islands.3 There doesn't seem to be a consensus about the origin of the name "Aleut". In 1907, Hodge said: "Aleut. A branch of the Esquimauan family inhabiting the Aleutian ids. and the N. side of Alaska pen., w. of Ugashik r. The origin of the term is obscure. A reasonable supposition is given by Engel (quoted by Dall in Smithson. Contrib., xxii, 1878) that Aliut is identical with the Chukchi word aliat, 'island.' The early Russian explorers of Kamchatka heard from the Chukchi of islanders, aliuit, beyond the main Asian shore, by which the Chukchi meant the Diomede islanders; but when the Russians found people on the Aleutian ids. they supposed them to be those referred to by the Chukchi and called them by the Chukchi name, and the Chukchi often adopt the Russian name, Aleut, for themselves, though asserting that it is not their own."1

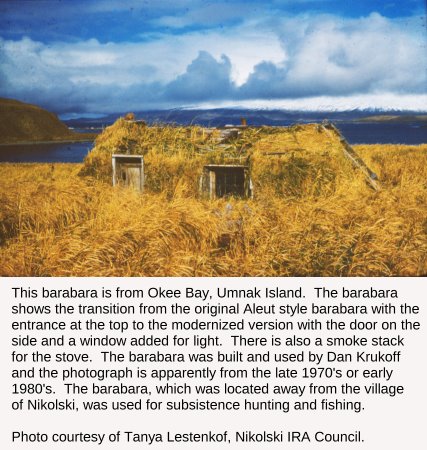

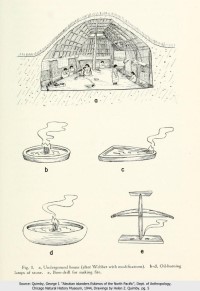

There is a movement among the Unangan to reclaim their ancient name and stop using the term "Aleut".3 The written legacy of several centuries that uses the Russian term, however, is very strong so that few people outside the region understand the term Unangan but do understand the term Aleut. Here we will use both Unangan and Aleut terms. Since the Unangan had no written language before the arrival of the Russians in 1741 and only began writing in Russian script in the 19th century, Russian words have been adopted for some common objects, such as baidarka (kayak, "iqyax" in Aleut); baidar (large skin boat, "nigilax" in Aleut); barabara (semi-subterranean house, "ulax" in Unangan); bidarki (a chiton); banya or banyu (steam bath) etc.

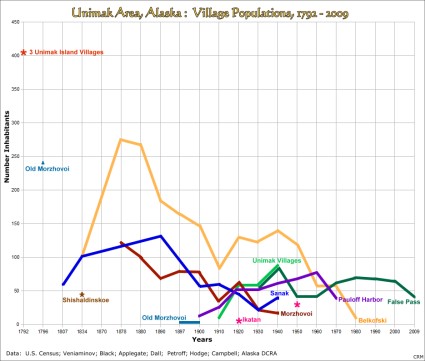

The above population graph shows very clearly the devasting consequences on the Unangan population by of the Russian conquest of the Aleutian Islands. Scores of villages were wiped out or abandoned and chaos reigned during the early years of the occupation. During these early years there was no official Russian government nor Orthodox Church presence. Rather, the first wave of Russians consisted of Siberian "promyshleniki", the equivalent of the American West's mountain men, who were intent on adventure and quick fortunes from animal furs. They used brutality and firearms to force the Aleuts to hunt sea otter pelts for them. The details of those atrocities will not be covered here but the extant information on this period can be read in the excellent account of the Russian occupation of the Unimak Area by Lydia T. Black.4

In 1898 Petroff had this to say about Unimak Island:

"Passing to the westward from Belkovsky the traveler first notices the snow-covered peaks of two volcanoes on Oonimak Island, of which the larger is Mount Shishaldin, rising to a height of 8,000 feet. Smoke rises constantly from the crater of this mount, and shocks of earthquake occur very frequently. The island is uninhabited, and has been in that condition for the greater part of the present century, though it is richer than many other islands of the Aleutian chain in natural means of sustaining life. Foxes are quite plentiful here, and sea otters frequent the reefs and points, but ever since (nearly one hundred years ago) almost all the inhabitants of four or five populous villages were massacred by the Russian promyshleniks a superstitious dread seems to prevent the Aleut from making a permanent home at Oonimak."2

The Russian occupation of the Unimak Area brought about large population displacements and migrations of the Unanagan people. The above map summarizes some of the basic population movements. Most large Aleut settlements were located on the north side of Unimak Island and lower Alaska Peninsula where there were rich subsistence resources. After the violence of the early Russian period and the forced entry into the market economy, most original Unangan villages were abandoned and the people moved to Morzhovoi and Belkofski which were locations that met the needs of the Russian sailing ships and trading posts.4

The graph on the left shows what is known about the historical village population trends in the Unimak area. Because of the chaotic conditions of the early Russian occupation period, no accurate data exists for Unimak area Unangan villages, nor most of their locations. This graph shows that the consolidation and abandonment of Unangan villages was well underway by around 1800.

Sanak is the only Unangan village that retained its original name throughout the historical period. The other Unangan villages were generally known by their Russian names since it was through Bishop Veniaminov and other Russians that information on the Aleut villages was put into writing. The Russian maps and charts of the time never located and named the villages but were mostly concerned with better charts for navigation. Morzhovoi and Belkofski were created and settled by the Russian administration for better management of their fur and ivory trade, where no significant Unangan villages existed before.

After the American acquisition of Alaska in 1867, there was a large increase in the populations of the remaining Aleut villages through immigration from other Aleut villages and a few European immigrants. This population shift reflects the huge impact of the sea otter harvest during the American period. But, this harvest was highly exploitative and brought about the extermination of the sea otter locally and therefore the crash of the village populations that depended upon the hunt. Some of the Unanagan villages were able to survive into the early 1940s by trapping fox and other land animals, but when the fur market crashed after the Great Depression, the villages lost population and were finally abandoned. People from these villages moved mostly to King Cove and Sand Point, but some moved outside the region.

In the 20th century, new villages were created at locations for the harvest and processing of local cod and salmon resources. These villages were Company Harbor (old Sanak), Pauloff Harbor, Ikatan, King Cove and False Pass. The disappearance of codfish in the late 1930s meant the eventual abandonment of Company Harbor and Pauloff Harbor. Then, changes in the salmon industry spelled the end of Ikatan and heavily impacted the sole surviving village, False Pass. In general, the history and fate of the Unimak area villages closely parallels the commercial harvest of the local renewable resource base.4

By the last quarter of the 20th century, all original Unangan/Aleut villages had been abandoned in the Unimak area. The local subsistence economy, which had endured for about 5,000 years, was finally brought to an end by the rise of the export economy and globalization.

Click on the above graph for a larger version.

Aleut Cultural/Social Change after Russian conquest:

"By the end of the 1700's, Aleuts were no longer in control of their own lives. Aleuts' precontact adaptive mechanisms for coping with changing conditions were wholly inadequate for handling the kind and magnitude of changes forced upon them by the Russian fur hunters. Imposed new social forms, religious institutions, and material culture had changed nearly the entire fabric of Aleut life. However, because the logistics and costs of foreign supply of foodstuffs to the Aleutians were prohibitive, the necessity of turning to the sea for the bulk of subsistence resources continued. To this day, the subsistence economy, especially in terms of the kinds of foods and resources utilized, the importance of cooperation and sharing, and the use of seasonal susbistence camps, remains the Aleuts' strongest tie to their pre-Russian past."17

"By the 1820's, some Aleut houses were built mostly above ground and had windows, side entries, interior metal stoves, and other modern trappings."17

The Aleut/Unangan acculturation process from the Russian period through the modern American period was studied by Veltre. This important study covers not only the Russian period, it also considers the impact of the World War II relocation of many Aleuts and the significance of ANCSA in empowering the communities in the Aleut region.19

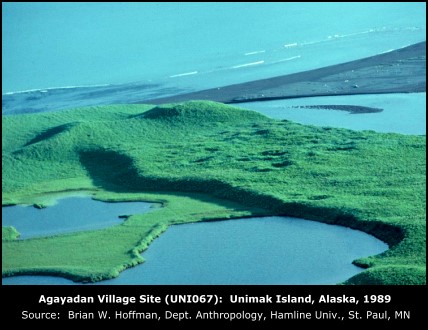

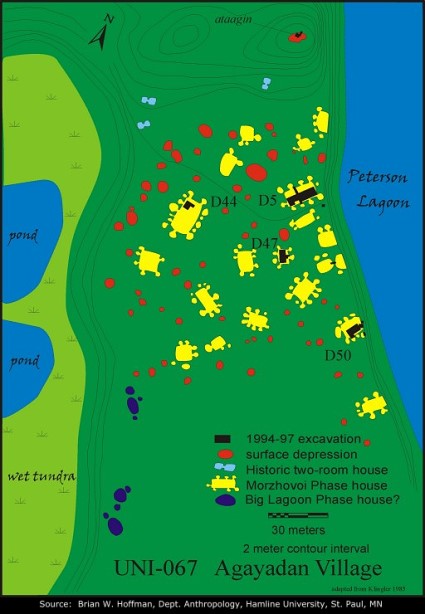

Archeological work on an Aleut village site on Unimak Island:

An Archeological study of an Unangan village site on Unimak Island called Agayadan was been done by Brian Hoffman in 1994-97. In summary, the study found that:

1) Agayadan had about 20 communal houses.

2) Site occupied between the years CE ~1300 - 1750.

3) House sizes ranged from 5.8 X 5.6m with 3 side rooms to 14.9 X 6.6m with 14 side rooms.

4) Site had an "Ataagin" or palisaded stronghold on high vantage point above village.

5) Agayadan was abandoned with a plan; the usable tools and building materials were salvaged and removed.

6) Each house had these special features: a) hearth, b) rock-lined basin, c) basin, d) storage pits, e) interior trench.

7) Family compartments were located in shallow interior trenches along walls.

8) Estimated two to four family compartments associated with each hearth complex.

"These dwellings were each occupied by multiple families who cooperated in some economic activities (heating the house and cooking some meals), yet operated independently in other activities (storage of surplus)."13 Please see the complete study for important details.

An historical overview of archeological research in the Unangan/Aleut region of Alaska was done in 2010 by Veltre and Smith:

"The Aleut region has the longest history of anthropological and archaeological investigations in all of Alaska. Although predating formal anthropological studies, the extensive ethnographic account by the Russian Orthodox priest Ivan Veniaminov in the early 1800s laid a solid foundation for scientific archaeological and anthropological investigations over the next 100 years, including those by William Healy Dall in the 1870s, Waldemar Jochelson from 1909 to 1910, and Aleš Hrdlicˇka in the 1930s. Following World War II, research continued, and the evolving political picture in Alaska gave Aleut people increasing influence and control over such efforts."18

Culture of the Unangan People

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

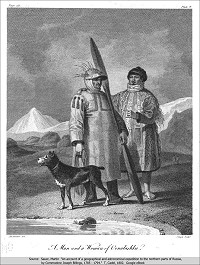

The above prints are from Captain James Cook's third voyage on the HMS Resolution when he visited Unalaska in 1778.

These prints are courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

The customs of the Aleut people were described in detail by the Russian Priest, Ivan Veniaminov, in about 1840. Father Veniaminov was the resident Russian Orthodox priest in Unalaska and took great interest in promoting the welfare of the Unangan people. He was also a good ethnographer, way ahead of his times, and a trained, unbiased observer. A portion of Veniaminov's work dealing with Unangan/Aleut customs and culture was translated by Ivan Petroff in 1884 and can be read here.

"Saluting the Light", was a custom that was performed by grown males in the Aleut community:

"This early custom is described as follows :The grown men were in the habit of emerging from their huts as soon as day was breaking, naked, and standing with their face to the east, or wherever the dawn appeared, and having rinsed their mouths with water saluted the light and the wind; after this ceremony they would proceed to the rivulet supplying them with drinking water, strike the water several times with the palm of their hands, saying:

“I am not asleep; I am alive; I greet with you the life-giving light, and I will always live with thee." While saying this they also had their faces turned to the east, lifting the right arm so as to throw the water, dripping from it, over their bodies. Then throwing water over the head and washing face and hands, they waded into the stream up to their knees and awaited the first appearance of the sun. Then they would carry water to their homes for use during the day. ln localities where there was no stream the ceremony was performed on the sea-beach in the same manner, with the exception that they carried no water away with them."14

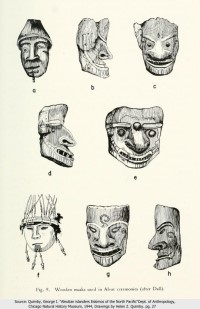

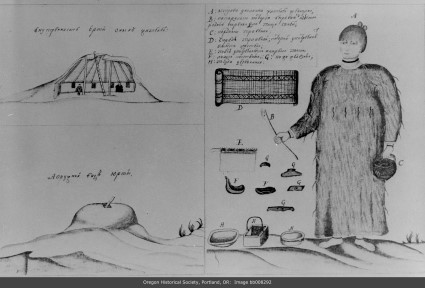

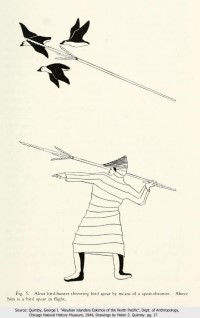

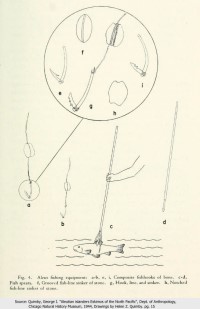

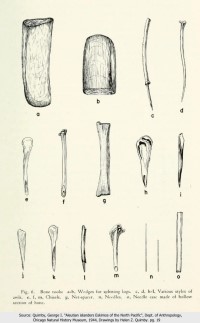

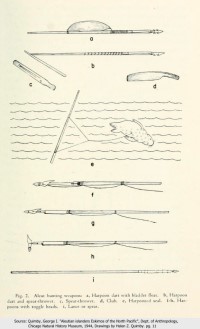

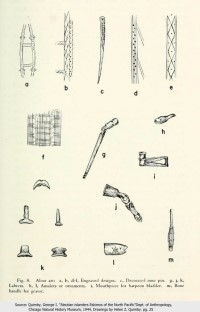

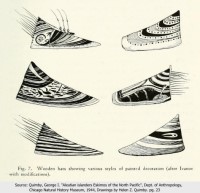

Examples of Unangan cultural artifacts can be seen in the line drawings below. These artifacts represent the main tools, implements, weapons, clothing and decorations used by the Aleut before the arrival of the Russians. A brief descriptive text that describes these artifacts was written by George Quimby from the Chicago Natural History Museum and can be read here. 7 The black and white print showing an Unangan man and woman (and a Russian dog!) was made by Martin Sauer on the Billings Expedition in about 1787. Click on the small images below to see larger versions.

|

Click on image to see larger version.

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

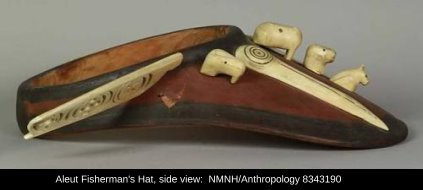

| Aleut Fisherman's Hat This Unangan visor was collected by J.H. Turner in the Aleutian Islands on April 9, 1892 and is now in the Anthropology collection of the National Museum of Natural History. These visor/hats were used by all Aleut baidarka paddlers when they went to sea. The visor protected the paddler's eyes from the glare of the sky and sun and made it easier to see clearly over the open water. These visors were used while hunting sea mammals and while fishing. Hat ornamentation was often very complex and told of the owner's status and wealth. |

|

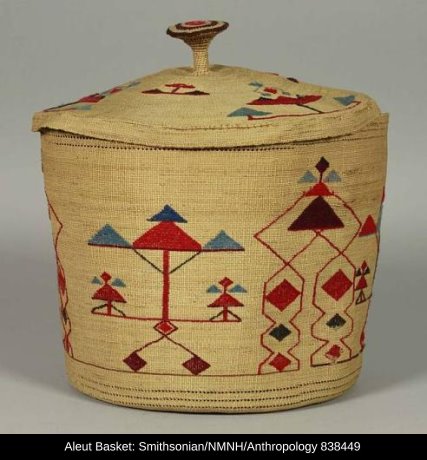

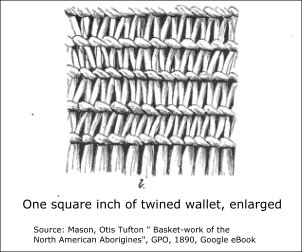

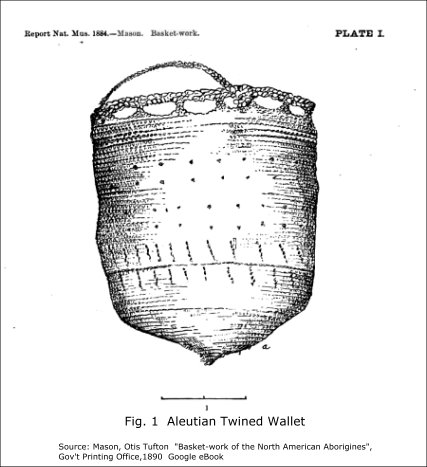

"Aleut basketry is some of the finest in the world, and the tradition began in prehistoric times. Early Aleut women created baskets and woven mats of exceptional technical quality using only an elongated and sharpened thumbnail as a tool. Today, Aleut weavers continue to produce woven pieces of a remarkable cloth-like texture, works of modern art with roots in ancient tradition. The Aleut term for grass basket is qiigam aygaaxsii."10"Aleut basket-making reached its zenith between 1850 and 1919. By the 1880s, Aleut weaving flourished, stimulated by the prospect of cash sales or trade for imported goods. .... The three major styles of contemporary Aleut weaving, Attu, Atka, and Unalaska are named for the islands where they originated. The Unalaska style basket is woven on all the other islands except Umnak. .... The majority of the State Museum's Aleut basketry collection dates from historic times. It consists of open baskets, cigar/card cases, basketry belts, napkin rings, basketry-covered bottles and inkwells, mats, fish baskets, thimble baskets, and "May" baskets."26

The Aleut basket on the right was collected on Attu Island in 1896 by Col. David D. Gaillard and now resides in the Anthropology section of the National Museum of Natural History. To see more images of this basket, please see the webpage of the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA). The DPLA has a large collection of Aleut/Unangan cultural artifacts and digital images that can be downloaded under the Creative Commons license.25

"Aleutian twined wallet of sea-grass. The warp consists of a number of straws radiating from the bottom. As the basket enlarges new straws are inserted, and the whole is held in place by twine made of two straws, which inclose a warp straw at each half turn. The cylindrical part of the vessel is of the diamond pattern in figure 2 <above>. The ornamentation is produced by embroidering with bits and strands of red, blue, and black worsted, in no case showing on the inside of the wallet. The continuous line between the diagonal stripes is formed by whipping with a single thread of worsted on the outer stitches of one of the twines of straw. Whipping with single thread in this ware is not common. The border is formed of the very complicated braid described in the text. Collected in Attu, by Wm. H. Dall, Museum number 14978."24

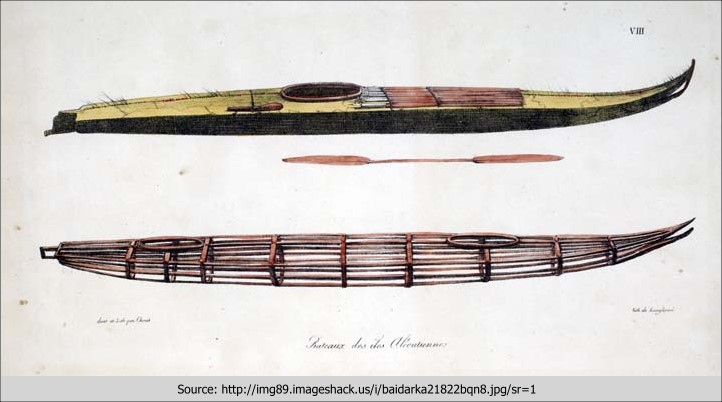

The Aleut Iqyax or Baidarka:

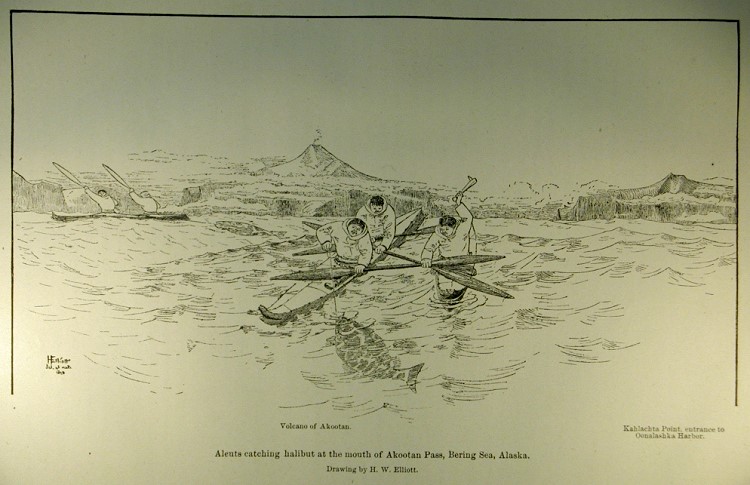

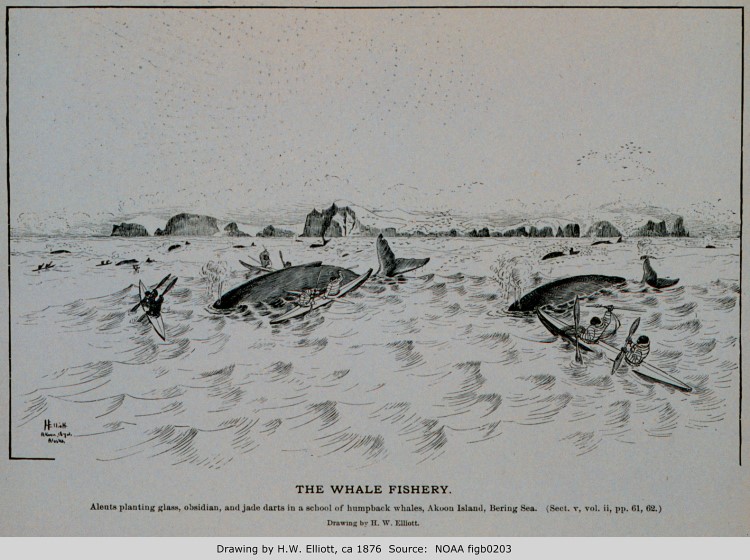

The Unangan kayak was one of the most highly refined sea-going vessels ever designed anywhere. The iqyax enabled the Aleut to travel great distances in relative safety, to pursue marine mammals and fish efficiently and to engage in war. Without the baidarka, the Unangan culture could never have occupied the entire Aleutian chain of islands and achieve its great stability and sophistication.

"The baidars, or boats, of Oonalashka, are infinitely superior to those of any other island. Its perfect symmetry, smoothness, and proportion, constitute beauty, they are beautiful; to me they appeared so beyond any thing that I ever beheld. I have seen some of them as transparent as oiled paper, through which you could trace every formation of the inside, and the manner of the natives sitting in it; whose light dress, painted and plumed bonnet, together with his perfect ease and activity, added infinitely to its elegance. Their first appearance struck me with amazement beyond expression. We were in the offings, eight miles from shore, when they came about us. There was little wind, but a great swell of the sea: some we took on board with their boats ; others continued rowing about the ship. Nearer in with the land we had a strong rippling current in our favour, at the rate of three miles and a half, the sea breaking violently over the shoals, and on the rocks. The natives, observing our astonishment at their agility and skill, paddled in among the breakers, which reached to their breasts, and carried the baidars quite under water; sporting about more like amphibious animals than human beings...... They row with ease, in a sea moderately smooth, about ten miles in the hour, and they keep the sea in a fresh gale of wind. The paddles that they use are double, seven or eight feet long, and made equally neat with the other articles."20

"The kayak developed as a hunting craft, its evolution a vicious circle encompassing kayak, hunter, and prey. One kayak was required to obtain the game to sustain and clothe the hunter while building another kayak, in turn required to hunt down the materials to build further kayaks: thus kayak evolution cycled forward from year to year. The kayak competed in speed, stealth, and stamina against a wide range of amphibious vertebrates---including fellow kayaks, both in peacetime and in war. In the North Pacific, after many thousands of years, the Aleut baidarka emerged as the most successful of the results."8

"Driftwood and the skin of sea mammals are the only elements used in the construction of a kayak. The use of bone pegs to fasten the pieces of wood disappeared during the nineteenth century and was replaced by another system of attachment: thongs made from the tendons of whales (or sea lions) wrapped around the pieces to be joined or passed through holes drilled in each of the two pieces and tied.

The sea mammal skins used to cover the kayaks were essentially the skin of the sea lion (Eumetopias jubata Schreber), which is thick and tough, or, if this was not available, for smaller craft (one-man kayaks), the skin of the common seal (Phoca vitulina L). This however, is smaller and not as strong. "22

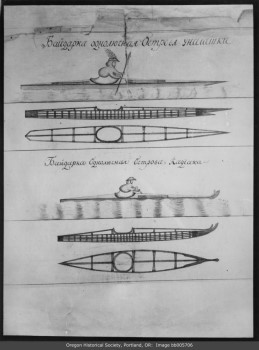

Baidarkas from Unalaska (Aleut) and Kodiak (Alutiiq):

These two kayaks had very different styles. The Aleut style was long and slender and it enabled the Unangan to travel long distances in the ocean safely and quickly. The Aleut style of baidarka has been copied by many modern kayak builders using modern materials.23

Click on image for larger version.

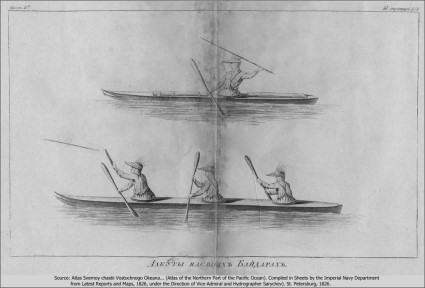

Aleuts in their baidarkas in this 1826 Russian drawing are hurling spears, one man using a throwing-board.

Click on drawing for a larger version.

The Unangan kayak was admired and sketched by a number of international travelers who visited the Aleutian Islands in the 18th and 19th Centuries. The black and white sketchs below were part of a series made by Henry Elliott in the 1870s showing Aleuts using kayaks at sea for fishing halibut, hunting whales and sea otters. A French voyage around the world (which has yet to be found in the literature) passed through the Aleutians and a sketch was made of the baidarka (seen below) that shows the outside appearance, complete with throwing board and arrows or harpoons on the deck. The complex flexible interior wooden frame of the kayak is also shown in detail. The skin of the kayak was made from Sea Lion or Hair Seal skins.

Over time, three types of baidarkas evolved. "The one man kayak (iqax in Aleut) was the most common form at the time of the discovery of the Aleutian Islands by Russian colonizers..... The two man kayak (ulluxtadaq in Aleut), which was still rare in the early nineteenth century, is mentioned by Cook, Levasheff and Langsdorff as being reserved for village chieftains with a "servant" to operate it, or is described as being used to train young men in hunting and navigation, under the direction of an experienced hunter.... The three man kayak (ulluxtaq in Aleut) is unanimously considered a later creation, linked to the presence of the Russians, and used to carry administrators, traders or priests from island to island. The foreigner then occupied the central position between the two paddlers."9

An excellent original study done by Joelle Robert-Lamblin with the expert help from Bill Tcheripanoff, baidarka builder from Akutan, can be seen here in English translation.

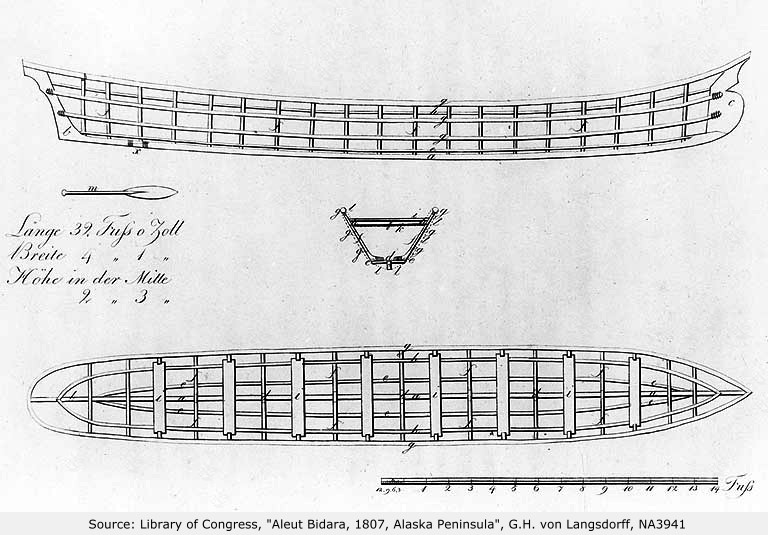

The Unangan/Aleut Bidara (nigilax) shown below is from the von Langsdorff expedition that traveled through the Unimak area in 1807. The bidara was a large skin boat capable of carrying many people. It had seats for 16 rowers but could accomodate many more passengers and cargo. It is similar in form and function to the Eskimo Umiak.

...the Aleutians make a sort of large open leather boat, called a baidar, which will hold fifteen or twenty persons. These boats were formerly the common property of a whole village, but they are now all in the possession of the Russio-American Company, and are used by them in their ordinary business; as, for example, for towing trunks of trees on shore, for carrying goods to and from their ships at their arrival or departure, or for towing home a whale, when one has been killed.12

Notes accompanying drawing: a) the keel b) the rear piece, which is fastened together with the keel c) the board, which rests on the keel d) cross laths which lie on the keel e) poles, which lie at the ends of the cross laths f) the ribs, over which the stretched skin is pulled, and which are fastened to the lower cross laths g) the upper edge laths, which are fastened to the stretched skin h) laths on the inner portion of the sides, on which the benches lie I) the sitting benches k) thong twined together, which are placed in 3 or 4 places under the benches, so that the baidar cannot break asunder in the waves. No rails are used for the fastening, instead the pieces are made fast with baleen or sinew. The entire skeleton, or framework, is finally covered with sewn-together seal pelts m) the steering paddle.11

The Unangan/Aleut people used the local wild plants extensively for food, medicines and fiber. Although much of the original knowledge about the use of plants has been lost locally, Aleut people still use some of the plants on a regular basis.

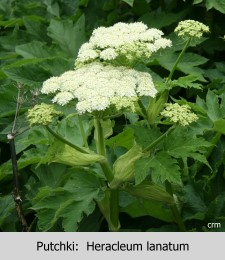

One of the most commonly used plants is the "Putchki" or Cow Parsnip, (saqudax') which is eaten by people, especially children, in the spring when the stalks are crisp and juicy. The flavor resembles a strong celery taste. Putchki was also used for fuel, poultice and tea.6 It often grows on old Unangan village sites.

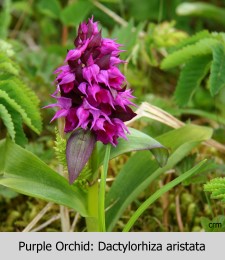

Another plant that was used for food is the Purple Orchid (quungdiix'), whose roots were cooked and eaten.6 This plant is one of the first to bloom in early spring time.

The fibers for the fine Aleut basketry came primarily from a common grass that grows luxuriantly along the beach. This grass is called Wild Rye Grass or Taxyux' in Unangan. This grass was also used for making carpets, mats, capes etc.6

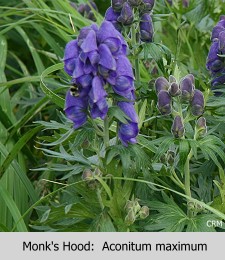

Whale hunting was done with the help of a potent poison made from a tall fall-blooming aconite called Monk's Hood or "Bumble Bee flower" (anusnaadam ulanquin). The poison was made from the boiled roots and was smeared on the harpoon tips that pierced the whale.6

Much more information on the local flora and its traditional uses can be found on the Unimak Geography/Plants page of this website here.

The traditional uses of plants by the Unangan people can be seen in more detail in a report published by CAFF (Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna) here.

References:

1) Hodge, Frederick Webb, Handbook of Indians North of Mexico, USGPO, 1907, pg. 36

2) Seal and Salmon Fisheries and General Resources of Alaska, chapter by Ivan Petroff, USGPO, 1898, pg. 196, Google eBook

3) Turner, Lucien M., An Aleutian Ethnography. Edited by Raymond L. Hudson, Univ. Alaska Press, 2008, pg. xiii

4) Black, Lydia T., The History and Ethnohistory of the Aleutians East Borough. Limestone Press, 1999. Each AEB village is covered in detail.

5) Dyson, George, Form and Function of the Baidarka:the Framework of Design, Baidarka Historical Society, Dean Anderson, 1991. (http://books.google.com/books?id=oGFHP-79tnQC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false)

6) Veltre, et al, "Aleut/Unungax' Ethnobotany: An Annotated Bibliography" CAFF Technical Report No. 14, 2006

7) Quimby, George I. "Aleutian Islanders; Eskimos of the North Pacific", Chicago Natural History Museum Anthropology Leaflet 35, 1944. (retrieved from the Internet: http://openlibrary.org/books/OL7151107M/Aleutian_islanders)

8) Dyson, George "Form and Function of the Baidarka: the framework of design", Baidarka Historical Society, Dean anderson, 1991, pg 2

9) Robert-Lamblin, Joell "The Aleut Kayak As Seen By Its Builder And User And The Sea Otter Hunt" 1980, found at: http://www.arctickayaks.com/PDF/Robert-Lamblin1980/robert-lamblin.htm

10) Wikipedia: Aleut People

11) Library of Congress: http://content.lib.washington.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/loc&CISOPTR=2247

12) Langsdorff, Georg Heinrich “Voyages and travels in various parts of the world: during the years 1803-1807.” H. Colburn, 1817, Google eBook

13) Hoffman, Brian W. (1999) "Agayadan Village: Household Archeology on Unimak Island, Alaska", Journal of Field Archeology, v.26, pp. 147-161.

14) Petroff, Ivan (1884) Report on the Population, Industries and Resources of Alaska., USGPO, Washington (section on Aleut Customs, translated by Petroff from Veniaminov's "Notes on the Ounalashka District") http://www.archive.org/stream/reportonpopulati00petruoft#page/n3/mode/2u

15) Maschner, Herbert D.G. (1999), "Prologue to the Prehistory of the Lower Alaska Peninsula." Arctic Anthropology, v.36, n.1-2, pp 84-102

16) Maschner, Herbert D., (2009), "An Introduction to the Biocomplexity of Sanak Island, Western Gulf of Alaska.", Pacific Science, vol. 63, no. 4, p.682

17) Veltre, Douglas W. "Perspectives on Aleut Culture Change during the Russian Period." (1990), in: Russian America: The Forgotten Frontier. Edited by Barbara Sweetland Smith and Redmond J. Barnett. Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma pp. 175-183.

18) Veltre, Douglas W. & Smith, Melvin A., (2010) "Historical Overview of Archaeological Research in the Aleut Region of Alaska.", Human Biology, Oct-Dec 2010, v. 82, nos. 5-6, pp. 487-506

19) Veltre, Douglas, W. (1999), "Environmental Perspectives on Historical Period Culture Change among the Aleuts of Southwestern Alaska." Proceedings of the 13th International Abashiri Symposium, Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples, Abashiri, Japan. pp. 1-12.

20) Sauer, Martin “An account of a geographical and astronomical expidition to the northern parts of Russia, Commodore Joseph Billings, 1785-1794.”, T. Cadell, 1802 Google eBooks, pg 155

21) Davydov, G.I., "Two Voyages to Russian America, 1802-1807", Trans. by Colin Bearne, Limestone Press, 1977 (see note on center pictures in center of book about Levashov; images from Oregon Historical Society)

22) Robert-Lamblin, "The Aleut Kayak As Seen by Its Builder and User and The Sea Otter Hunt.", 1980, located at: http://www.arctickayaks.com/PDF/Robert-Lamblin1980/robert-lamblin.htm

23) Dyson, George B. "Baidarka: The Kayak", Alaska Northwest Books, 1986

24) Mason, Otis Tufton "Basket-works of the North American Aborigines", Plate 1, Gov't Printing Office, Washington, 1890, Google eBook

25) http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=record_ID%3Anmnhanthropology_8384439&repo=DPLA

26) Hulbert, Bette, "Aleut Basketry Collection of the Alaska State Museum" in Concepts, a reprint of Northern Notebook No. 3, Technical Paper 10, October 1999.